2023 HORIZON No. 4 Fall -- Vow of celibacy

2023 HORIZON No. 4 Fall -- Vow of celibacy

View HORIZON by clicking on the online edition above.

Click to download or view the pdf version of the 2023 Fall edition of HORIZON.

Explore our HORIZON Library to search for articles by topic.

Find our Index of back editions here.

Published on: 2023-10-31

Edition: 2023 HORIZON No. 4 Fall

A graduate of a Catholic university once told me that the students at her university caught wind of a lavish seafood dinner that the sponsoring priests’ community enjoyed during a Lenten Friday fast from meat. “Boy, if that is poverty, bring on celibacy!” was their reaction.

More than anything the comment reveals that the outside world is fascinated by the vows. Like a wedding vow, the vow of celibacy is public. It’s meant to have meaning for the ones who live it and for those who witness their lives. Like any big commitment, the commitment to a life of celibate chastity deserves to be revisited now and then. In that spirit, HORIZON brings together several articles looking at both how people experience the vow and how they make sense of it theologically.

To keep it real, we also present the advice of Sister Lynn Levo, C.S.J., Ph.D. about how and why to take a sexual history. The vow of celibacy does not turn people into non-sexual angelic beings, so serious discerners need to consider this foundational aspect of themselves.

Besides this close look at the vow of celibacy, we also bring you four vignettes of parents responding to their adult children entering religious life. Each family response is unique, but parents do agree about a few things. Don’t miss their insights.

Besides this close look at the vow of celibacy, we also bring you four vignettes of parents responding to their adult children entering religious life. Each family response is unique, but parents do agree about a few things. Don’t miss their insights.

HORIZON frequently takes on big topics and we’ve done it again here: celibacy, sexuality, and family. To quote those cynical students: bring it on! Happy reading.

—Carol Schuck Scheiber, editor, cscheiber@nrvc.net

Published on: 2023-10-31

Edition: 2023 HORIZON No. 4 Fall

A new, large-scale resource is now available online for people who want to connect with religious, know more about their lives, or promote their way of life—Bold and Faithful: Meet Today’s Religious. For the first time ever, users can click on a map and discover which religious are in a given area, their events, and how to connect.

The new site also offers video, podcasts, articles, and comprehensive resources for promoting religious life, such as curriculum, infographics, fact sheets, and webinars. It brings together previously disparate resources by offering materials from its sponsor, the National Religious Vocation Conference, and five key collaborators: A Nun’s Life Ministry, Global Sisters Report in the Classroom, Called and Consecrated, and VISION Vocation Network. The site was made possible by the support of the GHR Foundation.

HORIZON readers are encouraged to use and publicize the site at:

tinyurl.com/MeetTodaysReligious.

The NRVC will offer the workshop “Behavioral Assessment 2” by Father Raymond P. Carey, Ph.D. at the Redemptorist Retreat Center in Tucson, Arizona, December 2-3. This workshop is open only to those who have taken Behavioral Assessment 1 and will build upon their experiences in assessments and interviews. Find details and registration at nrvc.net.

Three keynote presentations and a roundtable discussion are now available from the 2022 NRVC Convocation “Call Beyond Borders,” held in Spokane, Washington. Find them at youtube.com/NatRelVocationConf.

The three presentations also appeared in the Winter 2023 HORIZON. Members of the NRVC can download discussion guides for these videos in the Member Toolbox area of nrvc.net.

• Borders, Boundaries, and Catholic Identity: Three Approaches to Vocation Ministry by Father Ricky Manalo, C.S.P.

• Vocation in the Age of Migration, by Father vanThanh Nguyen, S.V.D.

• Here I am, by Sister Barbara Reid, O.P.

• Roundtable Conversation: Rewind the Future, featuring six men and women religious

Published on: 2023-10-31

Edition: 2023 HORIZON No. 4 Fall

MANY WOMEN AND MEN in the initial stages of vocation discernment feel called out of the self by Mystery, but they encounter intimidating obstacles. One of the most daunting in our culture is the belief that genital sexual expression is the sine qua non of human self-fulfillment. Given that widely-held belief, celibate chastity is radically suspect, and this undifferentiated suspicion enormously complicates the vocation minister’s task of helping others to make intelligent vocation choices.

Largely because I once shared this attitude, celibate chastity was the most difficult issue for me to address in initial discernment. I spent many nighttime hours wrestling with the realities of celibate chastity because to my mind, it was the obstacle, the stumbling block, and not just one question among many. My experience as a vocation minister tells me that others, both ministers and candidates, share the experience. In the rest of this brief reflection, I’d like to share some personal insights and anecdotes that have helped me to learn to love as a chaste and celibate religious man, to intentionally live the evangelical counsel, and to help others in their discernment as well. I’ll conclude with more practical advice.

But first it would be helpful to clarify just what I mean by chaste and celibate. All Christians are obligated to practice the virtue of chastity. Chastity is the moral excellence that helps us express emotional affectivity and human sexuality in thought, word, and deed, and in ways appropriate to our state of life. We gradually learn to be chaste by being chaste; it’s a developmental skill. Fundamentally, this means that if one isn’t married, then one doesn’t engage in genital sexual expression, and that the practice of moral excellence isn’t left to the giants of virtue. Chastity is, in a sense, every Christian’s “default setting.” Celibacy, on the other hand, means what your grandmother thinks it means. In this reflection, I’ll use the terms in tandem in order to highlight a fundamental frame of reference for vocation discussions.

The creation myths in the book of Genesis, Chapters 1-3, reveal a startling truth about human nature. According to sacred scripture, we know we are incomplete creatures who are made for communion with other creatures, with one another, and with God; and, what’s more, we don’t rest in that sobering knowledge, but strive to overcome this eerie sense of absolute solitude. Thus, our basic vocation is to love and to seek communion, which includes genital self-expression for the married. This is what we mean by erōs, or by having an “erotic nature”—we exist in such a way as to experience God’s own love through other things, people, and experiences.

Human nature is an embodied, sexual nature, an erotic engine, which can drive us and those whom we love toward God. For the chaste celibate, this means that we continually seek to integrate our physical, emotional, and spiritual needs in the company of friends.

Celibate chastity isn’t a static reality. It’s a hothouse flower whose integration requires a lifetime of hard work. Cultivation begins with the identification of one’s deepest needs and wants, and seeks to meet these in appropriate ways, ways that may sometimes cause intense suffering.

The ascesis of celibate chastity, for one who hopes to live it with integrity and sanity, doesn’t include the active suppression, or the attempted repression, of one’s erotic nature. By suppression, I mean “toughing it out;” by repression, that one attempts to ignore one’s sexuality, perhaps with a thin veneer of numinous spirituality. Both are cunning ways of short-circuiting sexual integration.

Two years before I entered the novitiate, I realized that I was straddling a fence. On one side was active discernment. On the other was the search for a lifelong spouse. Some people may, in fact, need to straddle the fence because they can’t climb down just yet for whatever good reason. But I needed to get off the darned thing because I was involved in a relentless pursuit of data. The hard reality is that I was temporizing, hoping that I would fall in love, set up house with my spouse, complete with a white picket fence, a Subaru station wagon, and 2.2 kids in the backseat. If I were already committed, went the rationale, celibate chastity would cease to be an issue.

The greatest fear that blocked my growth was that I would end up at best a sexually frustrated man, and at worst, a lonely and bitter one. So I dated. And I dated a lot—15 different dates in eight months! The longevity of these dalliances should’ve been a striking clue, but fear kept me closed to the real possibilities that both the chaste celibate and married ways of life offered. The only way to make a positive choice and to end the impasse was to try celibate chastity on for size, to see if it fit in all the right places, and to learn whether I could, in fact, live it joyfully and in freedom. So I waded in.

Since entering religious life, what may be shocking for some is that I have been in love. I’ve experienced the weightless infatuation, the visceral physical attraction, and the sharp emotional response. O Cosmic Irony, I found the flesh of my flesh, resplendent in shimmering humanity, after I’d made vows! It was enough to set me back atop the fence, or to cue the music and fade to the sunset shot of a couple walking hand-in-hand with a dog. My spiritual director asked me to remember the power of words, and to consider the place of sacrifice in a life of discipleship.

Father Timothy Radcliffe, O.P., former Master of the Friars of the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), once wrote that to make a vow is to commit oneself to an act of radical generosity in the present moment, being unaware of how the future will unfold. When a woman and man voice their wedding vows, they can only hope that with much hard work and even harder loving, their vision of life together will hold true. The same is true for the religious when making vows or the diocesan presbyter when making promises to his bishop. A single moment during which a few words are uttered affect the rest of one’s life because making vows and promises is a courageous act of hope.

Love is more than an emotion, although it is a most delicious one! It’s also an act of will and of choice, rather than something that falls fully formed from the heavens. Mature love is like a covenant in that it’s unconditional. When I was both in vows and in love, I was learning what it means to do so as a chaste celibate whose life is sculpted by the power of words. My newly found romantic interest revealed God to me. As one already committed, I realized that I would have to find a way to reveal God in the gradually calming storm of emotion, so that our friendship might survive, intuitively realize its own good and holy boundaries, and draw us both closer to God, who is Love itself.

In this way our friendship has been caught up in the life, suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and it endures to this day. Christ’s resurrection from death didn’t merely sound the final, triumphant note to his life. It was, rather, the leitmotif of his entire life. It hummed along just below the surface of the quotidian for those with ears to hear as he preached, taught, and healed in Palestine. His resurrection was already present in the sacrifice of his life for us and for our salvation.

When we consider sacrifice, it’s often accompanied by a big groan. Some take the consumer approach. I don’t have enough for both the tablet and the phone, so I’ll take the phone and get the tablet later. Others think about it as something to be endured for a greater good, but only for a limited time, determined in advance. I gave up cigarettes for Lent. And, others just restrict themselves to the payoff. He sacrificed a fly to right field in the bottom of the eighth. There is no joy to be found in the embrace of sacrifice if you think about it this way, especially if you want to talk about celibate chastity as a sacrifice.

God uses the sacrifice of a man or woman’s sexuality in celibate chastity as a most precious gift to be used for divine purposes, hallowed and fruitful for others. The roots of the Latin word sacrificium include the noun sacrum, holy, and the verb facere, to do or to make. To sacrifice is to make holy with divine help.

We can’t know the greatness that will come from the sacrifice of our sexuality to God in celibate chastity, but we do believe that God will transform us into creatures who become, in the course of a human life, more and more diaphanous icons of Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit as our discipleship unfolds in Christian mission. Here is the joy in sacrifice, knowing that my sexuality will bear life for myself and others and will not produce an arid wasteland.

When I was growing up, my hometown newspaper included a column entitled, “Hints from Heloise.” Heloise answered questions like, How do I keep gravy from staining a tablecloth? What’s a good bee sting poultice? I offer here what I hope are similarly helpful hints for discussing celibate chastity with vocation candidates. I make no claims to originality, but a reminder of received wisdom is sometimes a good thing in itself.

Celibate chastity is a way of loving God and neighbor in a most vigorous manner. It’s not just a ministerial commitment, or an ascetical discipline. This is a far more fulsome vision of the gift and potential of human sexuality than either suppression or repression can encompass. It challenges us to integrate the physical, emotional, and spiritual facets of sexuality into a life-giving whole. Let me show you what I mean.

I studied for a few years in a diocesan seminary before I left and eventually entered religious life. During one of our formation meetings, a wizened faculty member discussed celibate chastity. He was certainly well intentioned and tried “to connect with the boys,” but his advice was crass and stilted. The sum of it was that we, the seminarians, should prepare to endure lives marked by “not getting any” (suppression) and should “offer your struggles up” (repression). Both approaches, as we’ve seen, severely reduce the shelf life of the chaste celibate’s sanity. What’s a better approach?

If we turn to sacred scripture for insight, we might start with Matthew 19:12. The passage is the church’s classic locus for its basic teaching of religious and clerical celibacy. Some are eunuchs because they’re born that way, some because people have made them eunuchs, and some have made themselves eunuchs, “for the sake of the kingdom of heaven.”

A better translation of the Greek is “because of the kingdom of heaven.” God has seized those called to a life of celibate chastity in a grip so strong and commanding that the only free response is an absolute, total, irrevocable gift of one’s whole self—body, mind, and soul. One can embrace celibate chastity only “because of the kingdom of heaven,” only because of God’s abiding presence in human lives, only because of one’s profound love of God and neighbor. You give your sexuality as a gift to God and allow God to decide what is to be done with it because of the kingdom of heaven.

To sum up, human sexual nature is an erotic engine that can drive us toward our neighbor and toward God if it is intentionally cultivated by integration of the whole person—body, mind, and soul. The daily living out of one’s sexuality sacrificed to God in celibate chastity “because of the kingdom of heaven” has the power to transform the disciple into a sign of the present kingdom, into an eschatological symbol of God’s powerful presence in a world marked by fading dreams. Celibate chastity helps us to become holy, as the Lord, our God, is holy, holy, holy.

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2004 edition of HORIZON.

Father Douglas-Adam Greer, O.P. belongs to the Dominican Friars, Central Province. He is the theology department chair and a teacher at Central Catholic High School in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Published on: 2023-10-31

Edition: 2023 HORIZON No. 4 Fall

By Sister Julia Walsh, F.S.P.A.

AS A MODERN FRANCISCAN SISTER who has professed the vow of celibacy, I have freely chosen to give God my whole self, including my body. It is a call and a choice that causes me to give my body to God. Even though I serve as a minister and companion to those who are discerning their vocation, the concept of call remains a mystery to me. How can I define and explain the modern call to celibacy? For me, the call is a wispy and soft summons at times; at other times the call is an urgent insistence, like an eruption within my heart.

When I was very young—before I could I read or write—I encountered God’s mystery and felt a profound sense of wonder and awe. From then on, my heart and mind were captured by the power of God. I was formed by my desire to know, love and please the Holy Mystery; my desire to align my life with Christ has influenced even more than the path I walk each day. My identity and my imagination have been propelled into possibility by the Divine.

Along the way, I came to know myself and understand that I was unique, different. As a child, I felt confusion and frustration as I discovered that others didn’t have the same type of faith and focus on God as I did. Later, it was a lonely struggle to be a teen who wanted to avoid trouble, perhaps only because I was afraid of how the trouble might hurt my relationship with God. Attending a tiny public school in the hilly farmland of northeast Iowa, this desire to avoid sin and the near occasions of sin made me into an odd adolescent who prayed about purity of heart and body and was rightly labeled boy-crazy by my peers.

I didn’t yet understand that the radical call to celibacy often requires one to be radically different from others. Celibates must be counterculturally available for Christ, so to point to the wonders of eternity, heaven. Since no spouse can claim us as their own, we must stay open to prayer and service at any time, to promote God’s reign.

Off at college, my desire deepened to foster and protect what was most precious to me—my prayer life and my relationship with God. At the same time, I struggled with the arrival of normal and natural romantic and sexual feelings that seemed to be in conflict with the texture of my nature and my attraction toward spiritual things. I wanted to date. I dreamed of being a mother and wife. Yet, a desire to protect my prayer life guided me to a graced clarity and understanding that the vocation of Catholic sisterhood could offer the best container for my spirit to grow and develop and enable a particular response to the lure of God’s love. I was hearing a call.

I entered the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration just a couple years after college, at age 24. As my idealism met reality, I came to a deeper understanding of the cost of my choice. I had to pay a lot to respond to the call. I knew that being a Catholic sister would be complicated and challenging. I knew I’d continue to fall in love; I knew I loved God most and was meant to give God my whole self. I knew that life without a husband or children could be lonely; I knew that life in community would be life-giving and meaningful.

Each stage and season of formation and development brings its own struggles, yet I persist. I persist because the freedom and joy are not dimmed by the challenges I experience. I persist because I am committed to my choice. I persist because I remain confident of the call. And still, I continue to contend with tensions.

I dreamed of pregnancy and babies in my 20s. Now that I am in my 40s, I have desires to tend to a home, a family. I imagine that as I age, I’ll seek evidence that I am leaving a legacy. I imagine I might wonder about being without children of my own. Certain struggles remain constant: longings for partnership and intimacy; desire to support and accompany those younger than me; an urge to share and contribute to the formation of life, goodness, and beauty.

I am grateful to have learned that, with God, I can co-create these things. I do this in many ways, including by hosting retreats and building community at The Fireplace, the intentional community in Chicago where I share life with a diverse group of people. I am grateful for the love I give and receive in community.

Once, while attending an exercise class, I was asked to introduce myself to a partner. I said what I typically do: “I am a Franciscan Sister.” My partner nodded politely, but then admitted she didn’t understand. We talked for a few minutes, and I learned that she was completely detached from religion and unaware of religious life. As society becomes increasingly secularized, I will continue to find myself in conversations where my identity is not understood.

I accept it now: people within and outside the Catholic Church have assumptions and misunderstandings about the vow of celibacy and about me. I’m not called to counter the misjudgments, but I am called to reveal Christ’s goodness and love by way of my life. Although I professed celibacy publicly and have offered myself to God freely for the sake of the church and the general public, I can’t expect that others will understand.

They cannot understand; many of my reasons for remaining within the complex and sacred tension of vowed celibacy are private. Reasons for commitment ought to be private and personal for each celibate, truly, as our commitment is grounded in the deep love and intimacy we share with Christ. In this sacred tension, celibacy intersects with the purity and emptiness of poverty; I detach and let go and remain free from clinging to possessions, all so that more Mystery can be shared. Yes, to be a consecrated celibate is a public and private commitment for God, for others, from me—the tension of being misunderstood and of my conflicting natural desires persists.

Ultimately I know my vow of celibacy as a faith offering, one that embraces the tensions of living as a creative and sexual being within this vocation. In the midst of the tensions that coexist with this choice, I continue to choose my vocation because I am given to God. I belong to God.

Sister Julia Walsh, F.S.P.A. is a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration who is part of The Fireplace Community in Chicago. She serves as a spiritual director and vocation minister. Find her at MessyJesusBusiness.com. Her memoir, For Love of the Broken Body, will be published in spring 2024.

By Father Kevin Zubel, C.Ss.R.

RECENTLY WHILE VISITING MY HOMETOWN of Austin, Texas I met up with a close friend and former coworker for a long walk followed by caffeine-fueled conversation at a downtown café. The talk quickly turned to memories of the earliest days of our friendship when, fresh out of graduate school, we worked together as accountants at the local office of a global professional services firm. In the intervening years, both of us moved on from crunching numbers: she to family counseling and I to religious life as a Redemptorist missionary.

As we laughed over tales of demanding clients and interoffice drama, we began to take note of a recurring theme we lacked the maturity to recognize when we were in our 20s: how sexuality permeated the professional world we lived in during our years in client service. My friend and I remarked on how the strategic use of sexuality, whether conscious or not, played into the power dynamics of Austin’s office culture during its rapid growth in the early 2000s. This was not the old cliché of sleeping one’s way to the top, but a subtle role subversion in which newer hires, radiating a sexual self-confidence, asserted a charismatic authority over even the most senior members of the companies we served. Most of our clients were high-tech startups, and so there was a constant scramble for talent and funding. This filled the city with recruiters and promoters who used their sexuality to capture attention and move within high-flying social and corporate circles. Those in professional service firms also quickly learned which client personnel were physically attracted to certain staffers and took this into account when scheduling projects.

Although I am still young in religious life, I can look back on these earlier experiences and recognize the impact of human sexuality on daily life beyond the question of relationships and intimacy. When I reflect today on the vow of celibacy, my idea of the vowed life extends beyond thoughts on what is sacrificed for the sake of embracing a vocation to religious life. For me, the vow of celibacy literally embodies the call to live my sexuality in a way that is creative, relational, and free for the service of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

In outlining the importance of the vow of celibate chastity, our Redemptorist Constitutions and Statutes state, “Those to whom the Father has given this gift of grace, are so captivated by what the kingdom of God offers them, that only by choosing this religious celibacy can they respond personally and fully to God’s love for them” (Cons. 59). Of course, the discipline and self-denial implicit in the vow of celibacy bear a real emotional cost. All religious know that, on the day of our vows, there’s no magic switch that makes the mirrors go dark and turns the people around us into shapeless, formless beings. As a celibate I still feel drawn to connect with people, to feel lovable, and there are moments of great longing for intimacy. As I travel further into my 40s, the struggle and sadness of the self-denial involved in the vow of celibacy grow deeper as I realize I will never enjoy the joys, challenges, and companionship of family life as lived around an overloaded kitchen table. I recognize the need to mourn the cost of my freewill denial of the human right to an intimate relationship that would unite me, in Christ, to a wife with whom I might have raised a family and shared the joys and struggles of daily life.

However, as with other forms of grief, consolation dawns the moment I accept the healing and empowering grace of the Holy Spirit, who is always guiding us to fullness of life. Jesus tells us that “unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat; but if it dies, it produces much fruit” (John 12:24). I don’t believe that Christian discipleship, whether in religious vows, marriage, or single life, demands the discipline of celibacy as sacrifice or demonstration of commitment for its own end. We are a people of Resurrection, so for us, every death is the seed for the life of something new.

Even in my short time as a religious, I see that the creative possibilities for promoting healing, renewal, and reconciliation within interpersonal relationships becomes the “something new” that is cultivated by the vow of celibacy. My community’s constitutions note that celibacy, “like marriage, though in a different way … signifies and embodies the love of Christ and his Church” (Cons. 57), and it is in the bond between Christ and his church where we find our greatest guide for how to love others in a spirit of gospel sexuality.

Meditating on the life of Jesus of Nazareth, I see a person who relates to others, both male and female, in a way that integrates human touch with a gift of self. To heal and animate both body and spirit, Jesus will touch the untouchable, gather children into his arms, and wash the feet of his disciples. In his encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well, Jesus supersedes the taboos of his society not only to put the woman at ease in his presence but to embrace her right to be genuinely and assertively herself. In the intimate moments between Jesus and those in need of healing, we see none of the manipulation through use of sexuality that my friend and I witnessed in our earlier professional careers.

Human sexuality holds tremendous potential for good and also for violence, domination, and division. Jesus Christ restores this power to its original purpose of building bonds, affirming dignity, and creating new life in abundance. To me, the vow of celibacy frees me and all religious to live this gospel sexuality as embodied and revealed in Christ. Our membership in the Body of Christ calls us to be physically present to one another in ways that heal, strengthen, and unite us.

The truth of this was revealed in the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic when we began to see physical closeness as a potential danger mitigated through safety measures such as social distancing and masking. When I contracted COVID-19, I grappled with the terrifying and heartbreaking reality that my very breath put others at risk. With human contact limited by necessity, we Catholics discovered how essential physical touch and presence are to the sacramental life. When I was restricted to offering prayers for the dying through a phone or tablet, and unable to anoint the sick by touch or laying on of hands, I felt that these sacramental moments, though retaining the full action of God’s grace, nevertheless lost much of their power of encounter. Never again will I take for granted the gift of the sacraments as moments in which Christ unites us to himself by uniting us physically, in time and space, with one another. The sacramental life binds us as the Body of Christ as the lived ideal of gospel sexuality.

I pray that God will sustain me in my vow of celibacy, giving me the courage and the wisdom not only to cultivate the necessary discipline and spirit of denial, but to strengthen me to follow the example of Jesus Christ in embracing the healing and empowering potential of gospel sexuality. Living in a society that urges us to curate virtual identities, all of us—especially our youth—confront impossible aesthetic ideals that make us feel ashamed of our bodies and identities. Racism, classism, and sexism all persist in ways that reveal the continuing struggle against forces that assault human sexuality for profit or for power.

By saying “I do” to the vow of celibacy, I am asking the Holy Spirit to help my confreres and me to offer a counter witness to these dehumanizing forces and, by our example, to help other Christian disciples to follow faithfully the example of our Redeemer, for whom no one was untouchable or unworthy of love.

Father Kevin Zubel, C.Ss.R. is the provincial superior for the Redemptorists of the Denver Province. Prior to that, he was chaplain to the Hispanic Apostolate in the Diocese of Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

By Sister Romina S. Sapinoso, S.C.

IF YOU FELL IN LOVE at this time in your religious life, is there someone you would be able to talk to about it? This was my question to a small group in the Life Commitment Program I took part in some time ago. We were all men and women religious, preparing for perpetual vows in our respective congregations. As we talked about the vow of celibacy, a memory came back to me of falling in love while already in temporary vows as a sister. I remembered the flip-flopping, crazy energy of the early stages of attraction wreaking havoc on my insides.

“You look beautiful! And glowing,” one of my sisters who hadn’t seen me for several months told me. I blushed, thankful that my dark complexion didn’t display red on my cheeks. I was a little surprised that what I was feeling inside was so visible on the outside. I was in love.

I had been prepped for this experience during inter-congregational novitiate sessions on healthy sexuality. It was bound to happen, presenters said. It wasn’t a matter of if we fall in love but when we fall in love, they told us. Falling in love was a given. And it happened to me after I had left the dating world and moved into a world of poverty, celibacy, and obedience.

Thankfully, I was in a healthy community situation with at least one trusted sister I could confide in. I had the awareness to recognize what was happening, as well as the grace to allow myself space for the crazy emotions of what I knew was a normal part of my sexuality.

Deep down, we all long for connection. It is who we are as human beings. We desire to be seen, held, and loved by another in a special kind of way. Father Ron Rolheiser, O.M.I. talks about sexuality as, “a beautiful, good, extremely powerful sacred energy given us by God and experienced in every cell of our being as an irrepressible urge to overcome our incompleteness, to move toward unity and consummation with that which is beyond us.” As much as I love my life as a religious woman, I feel my incompleteness on some days more than others. It shows its need to be filled by the incredible energy I feel drawing me to the person I’m infatuated with, just as a hummingbird is drawn to sugar water. Taking a vow of celibacy doesn’t mean I’m immune to these situations and feelings.

Before I refined my understanding of the vow of celibacy, I could see myself running away, putting as much distance as possible between myself and the person I was attracted to. Repression would have been the immediate response of my less mature self. Sticking around would have been too scary and risky. Thankfully, with opportunities for spiritual and emotional growth, God’s endless grace has bettered this part of me over the years. With this foundation—and my sisters’ modeling of healthy, celibate friendships in community—I could respond in integration instead of by fleeing or giving in.

In contrast to fleeing, living a healthy vow of celibacy means embracing and seeking deep, intimate connections with others. This is vital in any vocation, including religious life. But this means we also risk falling in love at some point. Saint Irenaeus says that what brings about the glory of God is each of us, fully human, fully alive. Falling in love is certainly part of that whole human experience. When it happens, the hope is that we are grounded enough to proceed with discernment, honesty, and compassion for ourselves and those we fall in love with, understanding that this is what it means to live as loving people, fully embracing life. We remind ourselves that our relationships are held and wrapped in God, who alone fulfills our deepest desires for intimacy. The practices of self-work, cultivation of real friendships and accountability in community, and the discipline of prayer enable me to choose to honor this vow each day and season of my life.

It’s still not easy, but I am aware now that running away or closing myself up to everyone to avoid temptation doesn’t serve celibacy’s purpose because then I also shut out all other possibilities of deep, loving, celibate friendships as well. And what is life without love and connection?

For those of us in religious life, falling in love comes with the territory of loving widely, but so does rising above its exclusivity. Our Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati constitution says, “As daughters of Elizabeth Seton, we value friendship. We take care to foster relationships that are loving and freeing while avoiding those which are confining and exclusive. During the inevitable moments of loneliness, we seek to learn how better to give and accept love.”

There is freedom in embracing the fact that religious life is not immune to loneliness and still saying yes to it—and in realizing that the cure to this loneliness doesn’t only reside in finally being in exclusive love with someone we are drawn to.

When we live celibacy in an integrated way, we can move into a more inclusive love. The exhilarating, incredible passions of falling in love can be offered and joined with the Source of our essence and being. Imagine that power. When given to God, this energy becomes formidable in service to our mission—to stand with those on the margins, fight injustice, and show compassion to the broken. This is easier said than done, but with a balance in other aspects of our lives, it is so possible and so fruitful. Celibate living has always been about finding my way back to the center, into that space of equilibrium and balance of knowing whose I really am. It starts with recognizing when I seek affirmation outside and cling to the compelling energy of infatuation. It is having the grace to acknowledge it, and consciously let it settle within me instead of rushing to get rid of it. Returning to the center means finding joy and beauty again in regular, everyday things, such as a beautiful sunset or a cool breeze on a morning walk. It is soaking in a feeling of profound love and contentment after the exciting waves of emotion from a new attraction calm down. When I return to the center, I can recognize that I truly, deeply love my religious life and that I am also truly and deeply loved.

I’ve learned that the most beautiful celibate people are the ones courageous enough to love despite the possibility of getting hurt. Relationships have the potential to break us open and reveal what’s inside. That is always quite terrifying. But when we get past this, we also open ourselves to a more immense, wider Love. Truly loving celibates say yes to this, time and time again, in vulnerability and freedom. They see the bigger picture: the vow of celibacy is about God’s infinite love for us translated into love and acceptance of ourselves and overflowing to love for the people we encounter.

In the end, the vow of celibacy is a way to live Jesus’ vision of a full life: “I came so that they might have life and have it more abundantly” (John 10:10). For me, this vow has been a gift that seamlessly weaves the fabric of my life into a beautiful tapestry of friendship, grace, and connections under the encompassing shelter of God’s abiding love.

Sister Romina S. Sapinoso, S.C. is a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati. She recently completed ministry at the Texas-Mexico border and is currently serving as an adjunct professor in the education department at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati.

Published on: 2023-10-31

AS WE PROGRESS IN OUR UNDERSTANDING of what it means to be fully human and sexual, it becomes clearer that sexuality is far more complex, comprehensive, broad, rich, and fundamental to our human existence than simply genital sex. The word sexuality comes from the Latin word sexus and suggests that we are incomplete, seeking wholeness and connection. In essence, sexuality is the divine energy within persons moving them to connect with others.

It is important for individuals to be aware of who they have learned to be sexually if they are to make informed decisions about how to live healthy adult lives. This makes it imperative for vocation directors to understand potential members’ sexual histories to assist them in discernment. To understand a person’s sexual story requires time, opportunity, and a vocation director and psychologist working together. Taking a sexual history is an important, complex task best accomplished in more than one way, with more than one person and at more than one time.

One’s mindset or perspective matters for any undertaking, and this is particularly true for taking a sexual history, the term I and other psychologists use for coming to learn a person’s sexual story. I suggest four essential attitudes for those charged with obtaining information about an inquirer’s sexual and affective life.

This approach—rather than an evaluative, judging, or pass-fail perspective—is helpful. To effectively discern a vocation, people need to be aware of their sexual history or who they learned to be sexually and affectively, and they need to be able to share their story with those accompanying them. By conveying an understanding that all people are in process, vocation directors help discerners see that a sexual history is an opportunity for increased self awareness through self disclosure, rather than a matter of having “right answers” or passing a test.

Vocation directors need to keep in mind that taking a sexual history is not just about the past, but it is also about now and includes what is happening with them and the inquiring person. This requires that vocation directors have a solid understanding of healthy, integrated sexuality, that being sexual is more about connection with others in various ways than having sex, and that taking a sexual history is an ongoing process that will happen formally and informally now and throughout the formation process.

Third, vocation directors and inquiring persons need to be aware that this is not an us-them task. Rather, the inquiring person and the vocation director are sitting side-by-side on the same side of the table, looking at an individual’s sacred sexual story as a way to assist the individual to grow in self awareness about this essential aspect of self. Ultimately, the information gleaned from a sexual history will help individuals discern whether living a consecrated life of celibacy in community is the best way for them to be authentically human, to love and be loved, and to give their gifts in service to others.

Finally, taking a sexual history involves at least three persons: the discerning individual, the vocation director, and a competent psychologist who will, as part of his or her clinical assessment, actually conduct the thorough, formal psychosexual history.

Learning a person’s sexual history is an ongoing process that is about both the past and the present, happening not once but throughout the formation process. That said, I would like to discuss some fundamental questions: why take a sexual history, what is the role of the vocation director and of the consulting psychologist, what does a sexual history entail, how can it help the individual and the community, when should it happen, and how best to prepare for it? Finally, I will address some challenges for vocation directors as they approach this task.

Regardless of one’s chosen lifestyle, everyone’s first vocation is to be human and therefore, to be sexual. And each person has a sexual story, a sacred sexual story, with positive and often not-so-positive experiences. A sexual history can help people be clearer about who they learned to be sexually. It is one way to identify where they are and what areas may need to be addressed either before or during formation and beyond. An up-front approach early in their discerning journey may assist individuals to be more comfortable being in-process and unfinished (not an easy notion for a culture that promotes being all together and not self disclosing). An open approach also helps people talk about what they’re working on in their development.

Individuals can take this time to identify their positive learnings and development and to be grateful for and build on them, as well as name any mistakes, abuses, and subsequent consequences (e.g., shame, poor self esteem, lack of trust). A good sexual history will help the individual and the community to identify potential strengths and challenges that will likely be part of the candidate’s discernment and formation.

In addition, taking a sexual history and talking about sexuality raises the individual’s awareness that women and men religious do not leave their humanity or sexuality behind, that they are fundamentally called to love and be loved. It also offers an opportunity to address some myths, such as: celibate means not being sexual, being sexual requires being genital, or that intimacy is optional for vowed religious.

Finally, the multiple conversations entailed in taking a sexual history may help uncover a hidden and often unconscious motivation for religious life, such as a desire to escape one’s sexuality. Individuals might be avoiding an aspect of their sexual self (such as a lesbian or gay orientation or compulsive cybersex use), or they may be trying to rid themselves of sexual shame resulting from past abuse or behavior. Uncovering unconscious motivations and discovering healthier motivations is essential to freely choose a celibate life in community. It will also free discerners to utilize their sexual energy to form healthy, intimate, mutual relationships with both men and women, within and outside the community.

Sexuality, the all-encompassing energy in every one of us that moves us to seek connection, includes three aspects, each with multiple sub-aspects: primary sexuality (embodiment, sexual orientation, gender identity), genital sexuality (genitality and sexual expression), and affective sexuality (emotions, boundaries, relationships, intimacy, friendships, mutuality). Given this broader understanding of sexuality, it becomes clearer that taking a sexual history informally and indirectly begins from the very first contact the vocation director has with an interested person. It begins with what the vocation director sees (e.g., how the individual dresses and cares for his or her body) as well as how he or she experiences the person (e.g., warm and trusting or cautious and distant). To observe an inquirer well requires adequate knowledge of the various aspects of being sexual and a sense of ease with oneself so that the vocation director can use his or her energy for observation.

There are also more direct ways that vocation directors can explore an individual’s sexual and affective life: structured interviews, live-in experiences, guided written autobiographies, and letters of recommendation. One way to understand a person’s sexual history is to ask him or her questions about various aspects of life, to conduct an interview. I encourage a structured interview, that is, asking the same basic questions of each person. The structure affords an opportunity to develop a sense of how people respond and to sharpen one’s skills.

Regarding the content, I strongly suggest that vocation directors focus their questions on the affective and relational life of the individual. Before asking any sexual history questions, however, the inquiring person needs time to get to know the vocation director and begin to trust him or her. How long this takes depends on the individual. Trusting is not automatic and is even harder to achieve in today’s climate because of the violations of trust that people have experienced personally or are aware of. For fruitful self disclosure, it is important to prepare the individual for self revelation on topics such as prayer life, relational life, experiences of service to others, and especially to expect conversations related to sexuality during this “getting to know you” phase of exploring religious life. Showing that you talk about these same topics with everyone can help put a person at ease. In addition, the vocation director’s personal ease or lack thereof will either encourage or discourage the individual’s self disclosure.

Another effective tool is an autobiography written by the interested person to be shared with those involved in admitting candidates. I suggest asking the person to answer questions about aspects of their sexuality. A major focus should be on their affective life. This portion can respond to well-defined questions about the individual’s relational life (family, friends, co-workers, supports) in order to get some sense of how they see themselves in relationship to others. Although these same topics and questions will be covered in-depth by the consulting psychologist, having an autobiography is one way to ascertain whether a person is consistent.

Again, by giving each person the same task and guidelines, vocation personnel will be able to examine how people respond and thus sharpen their assessment skills. Noncompliance or avoidance of certain areas will suggest areas for further exploration. Although much can be gained from a person’s autobiography, it also has limits. Self reporting can be biased, intentionally or not, as most people want to put their best foot forward. This type of inquiry is best supplemented by seeing candidates in action and also hearing from people who know them. When a person is a serious candidate, the community usually asks for honest, frank appraisals from those who know him or her. Rather than asking for a general letter of recommendation, I advise asking people to address specific areas. These letters are more likely to offer specific, valuable information about the person.

Short live-in experiences are another way to understand who a person has learned to be. These are particularly valuable as a means of seeing how a person responds to certain situations and how he or she interacts with others. They allow you to assess if the person’s sense of self resembles what you see as they interact with other potential candidates and with the community.

Likewise, a live-in affords discerners an opportunity to see how the community functions. Discerners can then talk about impressions and experiences. For some people, articles about sexuality or celibacy may be helpful during a live-in as a means to explore ideas, beliefs, and attitudes about sexuality and consecrated celibacy.

To effectively explore another’s sexual story, vocation personnel need to prepare through ongoing opportunities for growth, support, and challenge. [Note: the author regularly leads a psychosexual workshop for the NRVC.] Opportunities should help vocation directors:

Once a person is considered a serious candidate, most congregations require some form of psychological assessment, which most often includes both psychological testing and an extensive clinical interview by a competent psychologist. The psychologist in most cases shares his or her findings with the candidate and with the community representative designated to receive such reports. I believe that the consulting psychologist plays an important role in helping the individual and the community to understand his or her sexual history and is the best person to be assigned the task of doing an extensive sexual history.

A good psychologist has expertise in making inquiries and maintaining a confidential setting. Well-trained, skilled psychologists will have experience exploring sexuality and will not be timid about asking difficult and personal questions. They are more likely to recognize and cope with resistance. Because of the confidential nature of the relationship, a person may speak more openly. And if a person shares something that he or she doesn’t want the community to know, the candidate can then choose not to release the report. Although this would be a red flag for most congregations and will most likely terminate the process of entering, it does protect the individual.

Because the consulting psychologist is an agent acting on behalf of the community, it is important that the community be clear ahead of time about what it expects in content and process. The community should clearly spell out what it wants to know. It is very helpful if the community shares its understanding of religious life and what it takes to live a healthy life of consecrated celibacy in community. The community cannot assume that a psychologist understands religious life and consecrated celibacy. Even with experienced clinicians, it is essential to have a frank conversation about the content to be explored in a sexual history. Lastly, the process of sharing the information with the individual and the community needs to be clearly understood in advance by all concerned.

A sexual history should explore each of the three aspects of sexuality: primary, genital, and affective and should include questions to explore healthy development as well as any deviant sexual development or behavior. A sexual history needs to address these fundamental questions:

Again, I recommend that an extensive sexual history be performed by a consulting psychologist. The vocation director does best to focus on the individual’s affective and relational life. I suggest that the following areas be explored by the psychologist.

To break down a sexual inventory even further, I offer the following categories for exploration. These were developed by Father Stephen J. Rossetti and Carmen Meyer of St. Luke Institute. They are part of the unpublished St. Luke Institute Psychosexual Interview, and I use them with permission.

Being able to work effectively with candidates to religious life will require a solid understanding of healthy sexuality, of how to promote ongoing healthy development, an awareness of your own psychosexual journey, and a capacity to sensitively and directly inquire about another’s sexual history. To work effectively with the increasing number of people from cultures outside of the United States, vocation personnel must be capable of suspending judgment. They must be aware of cultural and age differences and what is appropriate for the individual. Furthermore, vocation personnel must be able to collaborate with discerners, formators, leaders, and professionals. They need to process important information with community leaders (those with a need to know), be able to seek and utilize the expertise of professionals, and above all assist those in discernment to use their sexual history for awareness, acceptance, and appropriate action.

An authentic intercultural perspective is inclusive, requiring us to look both at how we are different and how we are the same. Although individual cultures have distinct understandings and perspectives regarding sexuality, there are also some fundamental understandings that cut across cultures. Vocation and formation ministers need to know what is fundamental to a solid, psychospiritual understanding of being human and sexual.

They also must be able to share this understanding with those seeking entrance into religious life. My experience in Central and South America, Mexico, Ireland, Canada, and Australia supports foundational understandings that are relevant to all cultures, as well as some diverse perspectives that need to be noticed, understood, and sometimes even challenged.

At no time in our recent history has promoting healthy, integrated sexuality for women and men religious been more important and necessary. For our religious communities to thrive, we need healthy members. Taking a sexual history of candidates and doing it well is a step toward fostering healthy integrated sexuality, essential for healthy adult living.

A version of this article first appeared in the Summer 2004 edition of HORIZON.

Sister Lynn M. Levo, C.S.J. is a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet and a licensed psychologist, lecturer, and consultant. She has presented workshops nationally and internationally on sexuality, celibacy, relationships, intimacy, and mutuality in community. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of New York at Albany, completing her clinical training at The University of Kansas School of Medicine.

Published on: 2023-10-31

If an adult child is happy in religious life, more often than not, parents will be glad their son or daughter has found their bliss. Pictured here are Michael and Lori Williams, with their daughter (center), Sister Kelly Williams, R.S.M. Photo courtesy of Lori Williams.

If an adult child is happy in religious life, more often than not, parents will be glad their son or daughter has found their bliss. Pictured here are Michael and Lori Williams, with their daughter (center), Sister Kelly Williams, R.S.M. Photo courtesy of Lori Williams.

EVERY PARENT IS UNIQUE. Every parent’s response to an adult child entering a religious community is also unique. The response is connected to many layers of emotional concerns, some that cannot even be named: hopes and dreams for their child, good or bad experiences with church figures, expectations and concerns about their own aging and the aging of religious communities, expectations regarding family time, desires for grandchildren, and sometimes even a concern that their own lifestyle is perhaps being rejected. It can be complicated, and adding to the complexity is that responses can be mixed or muted.

Still, a few things are clear. Modern parents tend to have strong ties to their adult children, and no matter how faith-filled they are, few are willing to automatically favor a church vocation. Equally clear is that parents want their adult children to thrive. And if they see a son or daughter happily living religious life, they tend to support the choice, over time if not immediately. Most have questions and appreciate when communities take them seriously and put in the time to answer questions and build trust and friendship with them. The average Catholic does not know much about religious life, so parents frequently begin their contact with a blank slate or with misinformation.

HORIZON brings you the parent-reaction stories of two parents and two younger religious. Their stories first appeared in the Religious Life Today webinar series, now on the Youtube channel of the National Religious Vocation Conference, youtube.com/natrelvocationconf.

By Lori Williams, mother of Sister Kelly Williams, R.S.M.

MY INITIAL RESPONSE to our daughter entering religious life happened while she and I attended a youth conference when she was in high school. She and several other teens had gathered for Eucharistic Adoration. I happened to look their way briefly. In that moment, God spoke to my heart, “Will you be OK with my plan for her?”

Kelly had never been one to openly cry in front of others even when she was hurt. In that moment I saw her glowing smile and tears of peaceful joy. I quietly whispered to myself and to God, “Yes.”

Over the next few days, I began to process this extraordinary experience. I realized I had been given a gift, a window into the possibility of her future as a religious. I knew Kelly would be the one who needed to make that choice, and I would be the one to provide the space to do so.

Then I thought about the impact her potential decision would have on me. We have five sons and only one daughter. I would never celebrate her engagement or be the mother of the bride. She would not need me to be with her when she welcomed children into the world. She would have so many women to support her, to guide her, and to celebrate important moments in her life. I would no longer be her primary confidante. What place would I hold in her life?

I concluded that it would be selfish on my part to even try to hold her back. I had realized long before that night that our children really do belong to God. All that we are called to do, whatever that might be, is for a greater purpose and that purpose is to glorify the Creator. Kelly has so much to offer our troubled world, so much positivity, so much joy, and so much love for God and God’s people. It would be many years later and with prayerful discernment, that she joined the Sisters of Mercy.

There were some initial concerns among her brothers. Here is a sample:

1. How often would they get to see her?

2. Would she still get to have fun?

3. Would she get to choose her profession? (Now they know that in religious life it is called ministry.)

4. Does she have a voice on where she will live?

5. Will she have a car and what about car insurance?

6. Can they visit her?

7. Who will be responsible for her health insurance?

8. Will she have a personal cell phone?

When my sons brought their questions to me, I simply suggested they ask her instead. Soon they realized the Sisters of Mercy community is very welcoming. They see her on holidays, summer breaks, and family occasions. They all know they will be invited to attend her important formation events as well. They recognize that her voice is heard regarding how she feels called to serve, and they have visited her at many of her community homes. She is always on board with whatever fun activity is to be had when she is with them.

My mother also expressed misgivings regarding Kelly’s choice to enter religious life. Her most frequent question was, “When does she get her habit?” My mum’s youngest sister, clothed in a black habit, entered the convent nearly 60 years ago through a formidable black gate. Religious life was very mysterious at that time. For the Sisters of Mercy, much has changed since then. Mum realizes now that Kelly is very happy as a sister, she won’t need to cut her very long hair unless she wants to, and she is not required to wear a religious habit. (My aunt no longer wears one either.)

The 2020 NRVC study of newer members revealed that parent hesitation is not uncommon. Only 60 percent of the parents were “somewhat or very much” in support, and around one half of those favorable parents fell into the lukewarm “somewhat supportive” category. I had a hint of this reality through discussions with Kelly and some of the other newer members. As parents, we always want what is best for our kids. We especially want what will make them happy. It is so important to remember that God also wants what’s best for them and what will bring them joy.

I intentionally looked for ways to support and encourage Kelly as much as I could. I did a great deal of praying and tried to remember to invite God into this life decision process, just like I did with all our children. I had to come to terms with the fact that the average age of the Sisters of Mercy today is between 70 and 80 years old. Instead of focusing on this huge difference, however, I focus on the positive. I realized Kelly would be mentored with the wisdom of so many women, who, in their advanced stages of life, are still active in their ministries.

As a Catholic lay minister myself, I was blessed to have had a working relationship with the sister who would later be Kelly’s vocation minister. I felt very comfortable expressing my thoughts during our many conversations. It took away the mystery, and she was receptive to my suggestions about how to put parents at ease. It is so important to invite parents to share their concerns openly.

Technology has given us opportunities to stay in touch with Kelly and be informed about her life. It should be readily available to those in formation to keep in communication with their families. Through the Sisters of Mercy website and their social media, I was able to become very familiar with the formation process and other aspects of the community.

All these approaches have helped me to truly be at peace with Kelly’s decision to be a Religious Sister of Mercy. I can see very clearly that our daughter is not leaving her family. Through the grace of God, she is joyfully expanding it.

Lori Williams is a retired educator, a parish RCIA director, and the mother of six, including Sister Kelly Williams, R.S.M.

By Brother Luis Ramos, F.M.S., member of the Marist community

WHEN I THINK OF SERVICE, I think of my parents immediately. They definitely modeled and instilled qualities in me that made me open to a life of service. Watching them work in New York City Public Schools in teaching and counseling was a major example of service and responsibility. Their work was not always easy, but they were dedicated to young people. They also taught me to be grateful and to share. They are two very generous people, whether it is time, energy, or resources. I always see them giving.

Even though service and giving were important values for my family, my parents had a mixed reaction to my interest in and exploration of religious life. They sent me to Catholic schools from grade school to college, and they knew I was especially involved with the Marist Young Adult community. That was a really important group of people for me, with whom I regularly shared my faith.

When I started talking about joining the Marists, my dad said: “I kind of figured this was a possibility.” I was received into the Catholic Church while I was in college, which was a change for our family. We had attended Pentecostal and non-denominational churches my entire life. I became really attracted to Catholic worship and the sacramental tradition when I was in grade school. College seemed like the right point to make that transition.

My mom and dad had questions and concerns about religious life. They never resisted it or tried to hit the brakes on the process, however. They always gave me space, asked questions with care, and emphasized listening to the Holy Spirit. They both said they would never stand between God and God’s work in my life! I’m continually grateful for this response.

My parents had met plenty of Catholic brothers and had a basic sense of what life as a religious could look like. One concern of theirs was whether I would be independent. In religious community, we let go of some of our personal independence to become more interdependent. We don’t become religious robots, though. I always admired how the brothers I had met were very much themselves while belonging to something larger. Thankfully my parents experienced that, too, having met them.

Another concern was definitely the question of grandchildren. My parents were never ones to push a career or lifestyle onto me or my sister. They modeled what it looked like to be educators, members of the community, and a committed married couple. As time has passed, we’ve talked about the reality that I’m not looking to start a family. They would have welcomed that if it was a reality in my life, but they know it is not. They don’t make a fuss and they don’t drop hints, either. That would be really annoying!

Their ultimate concern is that I be happy, fulfilled, and connected to God. As my discernment continues in temporary vows, I am confident that we’ll keep supporting each other. As a family, we continue to learn together. I’m watching my parents grow as my sister and I enter adulthood. We’re each living different lives with their own circumstances and challenges. It’s a pretty cool vocational journey for us!

Brother Luis Ramos, F.M.S. is a member of the Marist Brothers and teaches at Archbishop Molloy High School in Queens, New York.

By Sister Grace Marie Del Priore, C.S.S.F., member of the Felician Sisters.

I WAS, FOR THE MOST PART, raised in a single parent household by my mom. My two sisters and I grew up with my mom, mostly in New Jersey. I think she was generally confused by my interest in religion. She had been raised Catholic but in a number of ways had rejected the church; we seldom attended Mass, and she voiced only negative opinions about the church. Despite this, I was drawn to religion at a young age. It was something I took initiative on—I went to Vacation Bible School with one friend and to church with another friend.

But I was also surrounded by secular values. I went to public school until college. My mom encouraged me to pursue a professional, competitive career so I could be independent and make good money. Overall, I wasn’t raised to be a religious person. As I got older, these attitudes became a part of who I was. I didn’t become actively Catholic until college.

In other ways, though, my childhood prepared me for my future vocation. For instance, I always did well in school, and it was partially due to my mother’s support. She encouraged me to challenge myself and believe that I could do it. She instilled in me a confidence in myself and my abilities that has carried me through many difficult situations. This has helped me as a sister, and it makes me want to do the same for others.

When religious life became part of my life, my mother had a number of concerns. Some were helpful in guiding me to make better decisions. Others were more reflective of her needs.

First, she worried that I was rushing into this decision. When I was first discerning religious life, I was in my young 20s. She cautioned me not to make big decisions in my 20s, as women change a lot in that decade. This was based on her own experience: she got married in her young 20s and it didn’t end well. But it was also good advice. At the time, I had barely finished school and hadn’t moved out on my own yet. I also hadn’t dated much. What if I did those things and realized that’s what I really wanted? A few years later, I revisited the idea of religious life, and I was ready to move forward with it.

I think my mother was afraid I was leaving her, like I wouldn’t be her daughter anymore. At one point, she told me I could do it if I didn’t change my name—I remember her saying, “I gave you that name!”—and if I didn’t move out of our home state, New Jersey, when I became a religious sister. She said this early on, but by the time these things happened, she was accepting of them.

My mother also worried that she hadn’t given me a good example of marriage, that I was renouncing it because I had not seen a positive, loving marriage at home. She’s been divorced twice, and neither relationship could be called amicable. I assured her that her experiences were not why I wanted to become a sister.

I think what helped my mom the most was time. As time passed, she saw how happy I was and was happy for me. She realized that she wasn’t losing me to the Felicians. She also appreciated that I was settled into something, and she valued the opportunities I had as a sister. But all of this took time.

It also helped when religious life, particularly life in the convent, became less foreign to her. When she was exposed to my life with the sisters, she became more familiar with my daily life. Meeting the sisters helped. The Felicians did a good job with reaching out to her, inviting her to events and dinner in the convent. Before I became a postulant, my candidate director came to our house for dinner, which helped my mother get to know the Felicians.

My family, particularly my mom, had a lot of questions. They were not so much against my choice as they were confused by it. I think communities can help parents, families, and newcomers to religious life most by simply answering their questions throughout the discernment and formation process.

Sister Grace Marie Del Priore, C.S.S.F. serves as an archivist for her community, the Felician Sisters of North America.

By Kevin Cummings, father of Father Evan Cummings, C.S.P.

FOR AS LONG as we could remember, Evan said he wanted to be an engineer. When he came home one Thanksgiving and declared that he felt called to be a priest instead, we were surprised but not stunned. We had always been open to a religious vocation for our two sons; we didn’t push it, but it always made the list of possibilities.

We were proud that he was considering a religious vocation, and at the same time we had a lot of questions. We had no idea what the process of becoming a priest looked like or what Evan would have to do. Would he finish his bachelor’s degree or go right off to seminary? Who would cover the cost of seminary? What would his life be like in seminary and after?

We started researching and found there wasn’t much information available for parents. Most of what we did find was along the lines of, “Congratulations! Pray for your child!”

This wasn’t entirely satisfying. Two things helped us. First of all, Evan’s vocations director came to Utah to visit us. We had him over for dinner and then sat on the patio and talked for a couple of hours. The relaxed atmosphere made it safe for us to ask our questions. The second thing that helped was learning that formation (the first time we heard the word in that context) was about on-going discernment. It wasn’t a single moment in time, but a process that would continue through the next several years.

Based on that first conversation, we realized that we had a lot to learn. Since we didn’t find any really satisfying parent resources, we decided to start a blog to record our experiences of Evan’s journey and to post answers to questions as we found them. The blog still exists at seminarianparents.com.

We dove right in and explored the nature of vocations, the role of a vocation director, the difference between a religious priest and diocesan priest, how long formation took, what the stages were, whether religious are happy in their lives, and whether or not we’d be able to talk to Evan. The big question (and the one that drives the most traffic to our site) is: who pays for seminary?

Through the blog, we heard from other parents and young people with questions similar to ours. Religious life is a mystery to most Americans. Most of us only know the priest as that guy on the altar every Sunday, and we only know religious sisters if some happen to minister in our community. Otherwise, everything we know about religious life comes from TV and movies.

There can be a clericalism that separates the priests from the people. Priests and religious are often seen as remote and unapproachable, so it’s natural parents think that they will lose contact with their child. Our experience with Evan has been quite the opposite. We’re able to talk to him frequently. More importantly, we were able to visit him in the seminary as welcome guests of his community. Through those interactions, we got to meet and spend time with several priests. Getting to know them gave us insights into what Evan’s life would be like.

After Evan began his discernment—entering the community in 2013—we made it a point to host visiting priests for meals as often as possible. Even though they weren’t in Evan’s order, they were able to tell us about their experiences, good and bad, of the priesthood. The more we were able to see the priesthood through their eyes, the more comfortable we felt with Evan’s path.

In NRVC’s 2020 study of new vocations to religious life, around 60 percent of parents were at least somewhat supportive of their children’s religious life vocation. Only 34 percent of religious said that they received “very much” encouragement from their parents when they first began discerning. A further 27 percent said they felt “somewhat” encouraged. This is among those who entered religious life. I have to wonder how many expressed interest and were so discouraged they stepped away. This low level of parental support represents parental fear and misunderstanding. As vocation directors, you are inviting a young person into a new and alien life. It is important that you help parents understand that life as much as possible. All of us share in the responsibility to make religious life less remote and mysterious.

It all started with that positive first interaction with Evan’s vocation director. He clearly understood that, in a very real way, Evan was contemplating leaving our family and joining the family of his order. In that instance, telling families, “Thanks! We’ll take it from here,” isn’t satisfying. Parents want to know that their child will be safe and well cared for. Communicating with parents in the early stages of discernment can make them comfortable and increase their chances of being supportive.

Kevin Cummings is the founder of seminarianparents.com and father of two sons, including Father Evan Cummings, C.S.P.

Published on: 2023-10-31

Published on: 2023-10-31

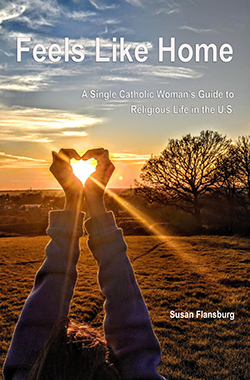

WRITER SUSAN FLANSBURG has worked with Catholic sisters for 20 years and has written for both VISION and HORIZON. Her book, Feels Like Home: A Single Catholic Woman’s Guide to Religious Life in the U.S. (independently published in 2023, CatholicSisterGuide.com), brings her wisdom and practical insights to women who are trying to find their “right home,” especially those who may be called to religious life. I accompany many young adult women in my position as director of vocation promotion and postgraduate volunteer ministry with the Religious of the Assumption Sisters, so I was excited at the prospect of this new book. I now plan to add it to my ministry resources.

WRITER SUSAN FLANSBURG has worked with Catholic sisters for 20 years and has written for both VISION and HORIZON. Her book, Feels Like Home: A Single Catholic Woman’s Guide to Religious Life in the U.S. (independently published in 2023, CatholicSisterGuide.com), brings her wisdom and practical insights to women who are trying to find their “right home,” especially those who may be called to religious life. I accompany many young adult women in my position as director of vocation promotion and postgraduate volunteer ministry with the Religious of the Assumption Sisters, so I was excited at the prospect of this new book. I now plan to add it to my ministry resources.

A strength of Feels Like Home is that it provides much of the information one needs in a short, concise book; it could be described as a handbook for discerners. Feels Like Home has four parts, each containing four focus topics. Throughout the book, we hear stories, advice, and recommendations from a variety of sisters who share their honest experiences of the discernment journey. I appreciated the many quotes and the authenticity of each person. It is evident how important it was for each vocation director interviewed for the book to assist women who are trying to discover their vocation. Their genuineness will inform and inspire those on a discernment journey.

The first section of the book focuses on the vocation stories of four sisters, each from a different type of religious order: apostolic, missionary, monastic, and cloistered/contemplative. I appreciated Flansburg’s exploration of the many possibilities available for living out religious life. This might be new information for some discerners, as often people have the wrong assumption that religious communities are all the same. Each story contains the sister’s “day in the life” schedule for readers to grasp entirely what a typical day involves. The quotes provide personal insights into the individual’s feelings about their daily commitments, prayer, and community life. After each story, Flansburg provides reflection questions to ponder and answer. These questions give discerners an opportunity for deep reflection on what they have just read and how it might resonate in their own experiences.

The second section, “Is Religious Life for You?” might be the most important part of the book. Here again, we have numerous quotes from sisters sharing personal experiences of their own discernment or of working with inquirers. This section highlights what each discerner should consider when beginning this weighty process: accepting personal invitations to Come and See events, seeking out a spiritual director, developing self-knowledge, taking time for deep reflection on what community or congregation one is attracted to, trusting one’s deepest intuition, and finally being patient. God will not be rushed in such an important life choice. In this section, the reflection questions are very direct and may challenge the reader. One can see throughout these sections how Flansburg, through her wise experience, and systematic proposals, encourages the discerner to go deeper into her personal life and beliefs.