2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall--What draws people to religious life?

2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall--What draws people to religious life?

View or download a pdf of the 2021 Fall HORIZON edition. Readers, please limit your sharing of material to 50 distributions or less. Contact the editor if you would like to share HORIZON material more widely: cscheiber@nrvc.net.

Cover photo by Adfoto.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON NO. 4 Fall, Volume 46

YEARS AGO, when I taught a grade-school religion class in my parish, I remember telling my husband that at least 50 percent of the questions in class could be answered with one word: “Jesus.” What will we be receiving at first Communion? Jesus. Why do we come to church on Sunday? Jesus. And so on. Fast forward a few decades and ask the question on the minds of vocation directors: What attracts people to consecrated life? Jesus.

If you boil down the much more sophisticated answers people give, for most it really does come back to a passion for living one’s faith in Jesus in a fuller, more intense way—living that faith in community, intentionally, publicly, as a committed Catholic who is at the service of the church and world.

Every vocation story is uniquely personal, and I can say that after many years of listening to these stories, they still move me, as a good story always will. There is a call. There is a response. That’s where the individual differences run the gamut, from full-throated resistance to a joyful yes. In the same way a good love story rivets us, the stories of attraction and falling in love with a religious community can also be compelling with their ups and downs and dramatic  moments.

moments.

May our exploration in these pages about what attracts people to religious life help you as you accompany men and women who are sorting out their own story. We’re all just grown up versions of those CCD kids years ago, still feeling a bit wondrous about this Jesus, who continues to inspire.

—Carol Schuck Scheiber, editor, cscheiber@nrvc.net

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

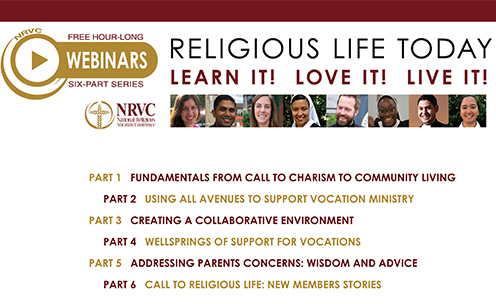

Webinars deliver information, strategies

Webinars deliver information, strategiesThe National Religious Vocation Conference is sponsoring a free webinar series entitled “Religious Life Today: Learn it! Love it! Live it!” The series began in September 2021 and will include five more sessions. Each session lasts one hour, consisting of approximately 20-25 minutes of expert presentations, followed by a live question-answer period. The webinars will also be available to view at youtube.com/NatRelVocationConf. The remaining five webinars are:

Using all avenues to support vocation ministry

November 17, 2021. Primary audience: vocation

directors

Creating a collaborative environment

January 13, 2022. Primary audience: religious institute leaders and diocesan vocation personnel

Wellsprings of support for vocations

March 3, 2022. Primary audience: Catholic organizations, parishes, campus ministers

Addressing parental concerns: wisdom and advice

April 21, 2022. Primary audience: parents

Call to religious life: new member stories

June 2, 2022. Primary audience: All supporters of men and women in consecrated life

The online store at nrvc.net is open 24-7 and is ready to serve you with timely, professional, quality products to help you minister well and build a vocation culture in your institute and the larger community.

Check out our bestsellers and hidden gems, each of them designed specifically to assist with vocation ministry. Products are discounted for NRVC members. Visit nrvc.net today and stock up.

Be sure to save the date and prepare your budget for the November 3-6, 2022 Convocation of the NRVC. It will take place at the Davenport Grand Hotel in Spokane, Washington and be hosted by the Pacific Northwest Member Area. Its theme is “Call Beyond Borders.” Details will be posted on nrvc.net.

The next World Youth Day will take place August 1-6, 2023 in Lisbon, Portugal. Pope Francis and millions of international pilgrims are expected to gather there to pray, worship, and celebrate their Catholic faith. Learn more about it at: lisboa2023.org.

Published on: 2021-11-02

by Nate Tinner-Williams

BACK WHEN I WAS PROTESTANT I understood the term “religious” to primarily indicate devoutness, a marker of genuine faith. A “religious” person, such as myself, practices religion intentionally. On the flip side, I understood the term to have a secondary (and opposite) meaning, denoting a commitment to the externals of religion with little or none of the internal necessities. That type of “religious” person, which I would never want to be, was all talk and no walk.

When I consider my attraction to life as a religious priest, my thoughts turn to the person who unwittingly exposed me to this way of life. One of the first “nuns” I ever met was at an Eastern-rite Catholic parish in San Francisco. I had grown up around countless Catholics. I had heard stories of women religious and had seen them in movies (Sister Act, in particular), but this was my first close-up encounter with religious life.

I should note that this sister was not an Eastern-rite Catholic. Like me, she was simply drawn to the beauty of Byzantine liturgy. At the time I was not yet Catholic and was still trying to make sense of the faith. Though I would not realize it until later, the witness of that sister in that unique parish—an anomaly within an anomaly—had a profound impact on my conversion and vocation.

One reason I was at an Eastern-rite parish was because of a lingering discomfort with Western Catholicism. As a diehard Calvinist for most of my adult life, I had viewed Roman Catholicism (and, by proxy, consecrated life) with a negative edge. Even after becoming more amenable to Catholicism, it remained hard to shake my disdain for the traditions I had criticized for so long. But seeing that sister in that Eastern-rite parish (along with a pastor who was a former Carmelite monk) eventually helped convince me that Catholic truly meant “catholic,” the glorious interplay of tradition and presence, as needs and desires dictate. If this sister and Carmelite monk could be bi-ritual, so could I.

I would come to understand that in Catholicism, this was to be my new normal—East, West, smells, bells, feasts, novenas, sisters, nuns, monks, brothers, and all the rest, co-existing and collaborating in God’s work. With each new word and experience came a new dimension of grace.

Eventually I would also discover that beyond the dichotomy of East and West existed various other layers of Catholic tradition, even ones within my own African-American culture. I would soon go from attending Divine Liturgy with measured trepidation to attending Gospel Mass with immeasurable joy (with a Black Augustinian priest presiding).

Deeper still was the history behind Black Catholicism, the witness of pioneers like Servant of God Mary Lange and Venerable Henriette Delille, the fortitude of Josephite priests such as Charles Uncles and John Henry Dorsey, and the fierce dedication of the National Black Sisters Conference to champion Black Catholic education amid horrifying opposition.

These were heroes of the Black Catholic story, and they were not just spiritual—they were religious!

I was received into the Catholic Church in December 2019, and as I began to discern my own vocation and consider the priesthood, God led me away from San Francisco and back to my starting place, where my radical ecclesial shift first began: New Orleans, a cradle of Black Catholicism.

I was to live in the city as a Catholic for the first time. There I began attending a Josephite parish for the first time, my first interaction with the only society of priests specifically serving African Americans. Naturally, a pair of Mother Henriette’s Holy Family sisters also lived in the convent across the street.

I joined the Josephites and the Holy Family sisters for daily Mass on occasion, and through one of them I received a supernatural message making clear that the Josephites’ mission was to be my own as well. I began the application the same day.

Within a week or two, the COVID-19 pandemic struck, plunging the world into a deep dysfunction just as I had begun to experience the sacraments and proximity to religious life. However, God does not make mistakes.

I’ve had a year and a half now to ponder what it means to live as a religious, to consider what I will give up, what I will gain, and what it will take to reach my goal. The past six months of that journey I have spent living with the Josephites themselves, giving me a clearer picture of their life pattern and ministry. I have learned of the trials faced by Black religious, as well as their triumphs and their hopes for the future.

The more I hear of the difficulties and struggle of religious life, the greater need I see for young men and women—especially African Americans—to take them up, helping to shoulder a burden that cannot be borne alone. I’m not devoid of fear, but I’m confident that I was called to a religious life, not to a rosy, easy life.

Moreover every time I read stories of pioneering and bold consecrated men and women, both past and present, I gain a new excitement, a new normal that says we need not cease being ourselves in order to be consecrated religious. I dream of a day when young African Americans will think it normal and obvious to answer the call of religious life, to serve as priests, doctors, nurses, scientists, teachers, scholars, activists, artists, writers, organizers, and innovators.

Do you dream with me? May God make it so.

Nate Tinner-Williams is a seminarian with the Josephite Priests and Brothers. He also edits the Black Catholic Messenger, blackcatholicmessenger.com.

By Sister Clara Johnson

I NEVER EXPECTED to join a religious community. It was a vocation I never considered because it was not a reality in my life. The only Catholic sisters I knew growing up were two retired Irish sisters who lived at our parish and who returned to Ireland before I finished grade school. How could I be attracted to something that didn’t seem like a viable option?

It was not until after college that the thought of religious life began to form. I was living in an intentional faith community while teaching in Magis Catholic Teacher Corps. I flourished in community life through this service program, and the experience sparked my initial attraction to religious life. God called me in this simple way. I had no idea what I was doing. I still did not know any women’s religious orders, and I was sure I was the only young woman around with this idea and attraction. Yet, through my spiritual director, I began contacting various communities and was joyfully surprised to find that I was not alone in my discernment.

I immediately set conditions on my discernment. I wanted to teach, I wanted to live near my family in California, and I could not imagine joining a community that wore a habit. But with God, there are no conditions. I was called to the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a community on the opposite side of the United States, with a habit, and no guarantee of teaching.

I entered in 2019 because I was attracted to community life, and I felt drawn to this way of living. But why have I stayed? The longer I live with the sisters, the more I realize how upside-down this life might seem. In a culture where autonomy is glorified and celebrated, I have chosen a life where my schedule, my ministry, and even those with whom I live—after dialogue and discernment—are ultimately chosen for me. These acts of obedience might seem stifling in a world where being in control has such great value. I find it difficult at different times to let go of these freedoms and choices and to place them into God’s control, trusting that God works through the community and those who are responsible for my formation in this life.

In the beginning, letting go of my identity and work as a teacher was incredibly difficult. Since college, my plan had been to teach for the rest of my life, yet I had to offer this plan to God. I grew up being told to follow my dreams and to pursue whatever I wanted, and this is a mindset that is not easy to change. Being a part of a religious order, I had to redefine my dreams. After teaching for several years, it was difficult to move into various part-time ministries as a postulant, none of which included teaching. Yet, the grace of this sacrifice was realizing that I was more than just a teacher. Through this sacrifice, I began to understand the deeper meaning of the Jesuit motto, Ad majórem Dei glóriam (For the greater glory of God). I realized that all of my works, great and small, could be offered for God’s glory. All these small acts, from cleaning, to prayer, to sacristy work, gained greater meaning in my life as I learned to orient them to God’s glory and not my own. Therefore something that was initially unattractive and difficult has become something that surprisingly draws me more to this life.

Before I entered the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, I knew the most unattractive part to religious life would be the separation from my family. Being from a close-knit family in California, it is constantly difficult to be so far away. This reality became acutely challenging when my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer last year. Although I desired very much to return home and support my mother and family, through prayer and discernment, I knew that that was not where God was calling me. God’s desire for me was to remain and to pray. This was not easy to accept. In my mind, I wanted to take control of the situation and to “fix it.” Yet, God was asking me for submission and trust. There were many tearful phone calls and prayers during this time, but through it I discovered an important role within myself. God taught me that I do not need to take control but rather to trust in God through my prayers, which drew me deeper into this life.

Community life had been my initial attraction to religious life, and it continues to be life-giving for me. Being a part of the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, I am able to see and experience the joys and challenges of intergenerational community life. While it is not always easy, these women are continually bringing me to greater holiness through their example and life. We are blessed to live on the same property as the retirement home for our sisters, and the relationships with these sisters have been some of the most important to me. Their example has taught me the importance of the centrality of prayer in our lives and that holiness is not achieved in a day or even over years. It is a lifetime journey.

Living in community has its challenges since all of us are human. We have moments of conflict, misunderstanding, and loneliness. Yet, there are also powerful moments where what it means to be a part of this community becomes clear. Last year, one of our sisters was hired at a new school as principal. Very quickly, it became apparent that the school needed a deep clean and reorganization. She asked for help from our sisters, and the next day I was amazed to see over 30 sisters from all over the area present to support her at her new school, cleaning every classroom and closet. To me, this is the blessing of community. In spite of our mistakes, disagreements, and challenges, our work for God unites us and allows us to build each other up.

While all these aspects of religious life are an important part of my attraction to it, the most vital parts for me are my prayer life and the spirituality and charism of my congregation. Pope Francis, on the World Day of Consecrated Life in 2016, stated, “The ‘marrow’ of consecrated life is prayer.” The longer I live this life, the more I understand this statement. Without prayer, I do not think I would be able to sustain living this life. It is my nourishment.

The charism of the Apostles is, above all, the most attractive part of this life. The charism is what moves me and motivates me. It is seen and felt in all of the sisters. The Apostle charism is rooted in devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. In 2021, for the feast of the Sacred Heart, the Responsorial Psalm was, “You will draw water joyfully from the springs of salvation” (Isaiah 12:3). For me, this is what attracts me and draws me deeper into this life: the water poured out from the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Through this life, Jesus invites me to approach him joyfully and draw life and graces from his heart and then to go out and share that love with others. Even with this truth and understanding, there are days when I feel disheartened, lonely, or misunderstood. There are days when I feel alone and distant from God. Yet God asks me to offer every moment, the good and the bad, to God’s Heart, and I’m learning this is what sustains me.

I am learning that my true freedom and ultimate happiness lies in uniting my will to God’s will. But this is, understandably, no easy task. Our foundress, Blessed Clelia, writes, “A vocation is a flower which is nurtured and made increasingly beautiful with the powerful sap of sacrifice.” The beauty of religious life comes from sacrifices we make every day: from ministry, to community, to family, to prayer. These sacrifices are made because we realize there is a greater longing in our hearts, a longing to unite ourselves completely to God.

Sister Clara Johnson belongs to the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. She is a canonical novice and lives in Hamden, Connecticut.

by Tucker Redding, S.J.

SHORTLY AFTER MY GRADUATION from Texas A&M University in 2006, I joined a group from St. Mary’s Catholic Center in bringing an elderly Franciscan friar to his new home. Father Curt ministered in the Catholic Center and was beloved by students. When we heard that he was retiring, we decided that it would be better to send a group of students to help him move so that he wouldn’t have to make the long drive alone. Little did I know how much of an impact this road trip would have on my life.

I always had this idea that guys who become priests know their vocation from a young age. I swear some priests were born wearing a Roman collar. Well, I didn’t grow up with that desire. Far from it! And because of that, I never considered the possibility of becoming a priest.

I grew up in a Catholic family but really took ownership of my faith when I was in college. Still, I never considered a vocation to the priesthood. Until, of all things, a cross-country road trip with an elderly Franciscan friar.

Along the way, we stayed at different churches and schools and met with members of different religious orders. I had avoided vocations events, but had God finally tricked me into attending one? Our first destination was New Orleans, and we went to visit the Jesuits. When I heard that at the end of a long day of driving we would have to listen to a presentation by a group of priests, I was annoyed. This is not what I was expecting! But much to my surprise, I was captivated by the talk. One of the Jesuit speakers had also graduated from Texas A&M, and his work abroad had motivated a deep desire to work with the poor and marginalized. He talked at length about the Jesuits: their community life, the variety of ministries that they engaged in, and how they seek to help those in need wherever they are. All of a sudden, I felt a spark in me. It never went away.

My accidental vocation-promotion road trip continued. The very next day we visited a group of religious sisters. Their vocation promoter talked about how discerning the religious life is like dating: you don’t just choose to marry the first person you see. You have to “date” different religious orders because they have different qualities, charisms, and personalities.

“What does that mean?” I wondered. I just assumed that all priests were the same. The fact is that I mostly only knew diocesan priests, who are the typical priests working in parishes and remaining in the same geographic area or diocese. And I didn’t feel called to that life. Other priests belong to religious orders, which each have their unique characteristics. When I learned that the Jesuits engage in ministries like teaching and social projects and move around a lot, that expanded my idea of the priesthood.

My surprising moments of grace didn’t stop with that road trip, despite the fact that I continued to avoid pursuing a vocation to the priesthood for years. Jesuits kept popping up in my life. Months later, a Jesuit priest came to the parish where I was working in Houston to give a Lenten mission. During his visit, I was reflecting on the vow of obedience that religious profess. It did not sit well with me. I didn’t like the idea of giving up control over what I did with my life. Well, without any prompting, this visiting priest made a passing remark to me: “You know what I love about the Jesuits? They really listen to your passions and let you do what you want.” Huh? That did not sound like the image that I had of a lifetime of rigid obedience. While I could now add a few caveats to his comment, it was a surprising moment of grace and insight. And it was exactly what I needed to hear.

With all these moments of unexpected grace piling up, I finally caved in. I told my pastor that I was thinking about the Jesuits, but I was still plagued by doubts. He asked me what I was actively doing to aid my discernment. I told him that I prayed about it often. He told me that prayer was key, but that I needed to aid my prayer by actively doing something, like meeting with Jesuits or going on a discernment retreat. He made me realize that God might send me all the signals in the world, but God wasn’t going to pick me up and take me to the Jesuits. God would never move me. I had to move.

I finally attended my first discernment retreat. (Well, I guess it was my second depending on how you count my cross-country road trip with Fr. Curt.) On the way to the retreat, I had a frank talk with God. “God, I’ve been on the fence for a few years now. I feel this desire, but I just don’t know what to do. Please, I have to know. I want to leave this retreat with an answer. Please let me leave with an answer.” I laughed to myself as I thought that it probably wasn’t going to work out that way. “Now that I’ve asked for certitude,” I thought to myself, “I’m definitely not going to get it.”

I was wrong.

The retreat lasted five days, with two days to meet Jesuits and learn about their life, followed by a three-day silent retreat. One of the best experiences for me was interacting with Jesuits and seeing the community that they shared. The brotherhood between Jesuits, the community life that I love so much now, was something that I had not experienced or expected.

The Ignatian retreat introduced me to praying through my imagination, and it was in those prayers that God helped to ease my mind. My doubts and fears transformed into peace and confidence. My final hang-up was the thought of giving up control. Who could dream bigger for my life than me? Why would I surrender that control?

How fortunate for me that this retreat was during Advent. In reading the stories of Mary and Joseph, God was telling me how wrong I was. Mary and Joseph surely had their own plans for how their lives would go, but God invited them to something more. God literally entered the world in the Incarnation because of their willingness to let go of control. As it turns out, someone just might have bigger dreams for me than I do for myself.

Overwhelmed by grace, I left that retreat with the certitude that I asked for. I entered the Jesuit novitiate six months later.

I have now been a Jesuit for almost 10 years. I have been to more places than I had ever been before. I have had the opportunity to meet some of the most amazing people. And I went from being an only child to having more brothers than I can count.

Have I experienced any doubts since the certainty I felt on that retreat? Absolutely. I continue to wonder if I can do this and if I’m worthy of it.

As I continue to seek those answers, I keep going back to what I learned throughout my discernment process. God is everywhere and speaks through those around me. I have to be honest with God and ask for what I want. But ultimately, God will never force me to move. I have to move.

Are any experiences in our life truly random? I used to be the kind of person to say, “Everything happens for a reason.” I don’t believe that anymore. Instead, I believe that God can give reason to all that happens. Including a cross country road trip.

Reprinted with permission from thejesuitpost.org.

Tucker Redding, S.J., is a Jesuit scholastic, originally from Texas. He is currently studying theology at Boston College.

By Sister Jessica Vitente, S.P.

I WAS DRIVING ON HIGHWAY 1 along the California coast. I saw a sign directing coastal access and decided to pull over and check out the coastline. That day I was wearing sandals because I did not anticipate going on a hike. But I grabbed a cold drink from the ice chest and followed a family walking ahead of me. The trail started with a set of stairs leading to a photo view access. To the left was a bridge. There I saw a couple who had just gotten engaged posing for a photographer. I felt butterflies for them. I could relate to the nervous excitement I imagined them to be feeling. Earlier in the day, I had been approved by our leadership team to profess first vows within a few months.

As I basked in that feeling, I wondered how long this hiking trail was and what else I might discover. I was curious about what was on the other side of the mountain. As I continued walking my thoughts wandered to how my own journey into religious life had started. I met the Sisters of Providence of Saint Mary-of-the-Woods at the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress in 2015. I became attracted to religious life because I found myself wanting more out of life. I wanted a deeper purpose. I wanted to contribute to making the world a better place. What I didn’t know was in what capacity I could find these things. My education and work were in business. I think at first I strongly resisted responding to my call because I felt I was part of the “nones” circle and did not want to be among the “nuns.” I had never met a nun in my life. The idea of fully committing myself scared me.

After meeting the Sisters of Providence at the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress, I went to my first Come and See weekend retreat at Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana. I met many wonderful and beautiful retired sisters, and I had a chance to meet other sisters who were around my own age. I remember going home and reflecting on the experience. I realized I wanted to follow in their footsteps, living life to its fullness in whatever shape, path, or form.

I was attracted to religious life, especially the Sisters of Providence and their way of living Providence spirituality. It was already how I had been living all my life. Their charism of love, mercy, and justice reflected how I had always wished the whole church would move forward. I had been searching for a circle of people matching my system of beliefs, and finally, I found them!

Because of my last three years in formation with the Sisters of Providence, I have been able to live life to the fullest. I have been given the opportunity to learn how to pause and live in a contemplative way. I have been able to do unimaginable things, such as travel in between states in the Midwest to get to know beautiful parts of Mother Earth, to teach ESL to men in jail, and to discuss social justice issues connected to the church. I also got to meet other young women in religious life through a group called Giving Voice.

Through my time with the sisters, I have been given the chance to deeply listen to God’s invitations and be responsive in mind, heart, body, and soul. This connection to the Divine allows me to bring the reign of God anywhere and everywhere—to the grocery store, gas station, jail, community college, university, or airport. The reign of God can come to a hiking trail, beach, or museum, for God speaks in mysterious ways!

During this period of my vocation discernment and formation, I also learned to negotiate with my “false self,” and uncover my “true self,” who is wonderfully and fearfully made by God. Through my formation as a Sister of Providence, I have learned to accept that my imperfections are perfect through my Provident God’s lens. Deepening my relationship with God has been a total gift. Prayer, grace, and pain have led me to freedom. It is convoluted. It is messy. And it is rewarding.

I thought I knew freedom before I started considering life as a Catholic sister, but I have had more spiritual and emotional freedom in these past three years with the sisters than I could have ever imagined. As our foundress Saint Mother Theodore Guerin said, “Have confidence in the Providence that so far has never failed us.” I have found that confidence.

I have hope for the future, both my future and future generations. I have hope that we can achieve gender equality and racial equality. I have hope that migrants will find safety and the imprisoned will find justice and mercy. I have hope that we will one day abolish the death penalty and that there will be better education for people in need. I believe that we can find ways to minimize the physical, emotional, and mental violence in our world. I am striving to be the best version of myself. Living a more contemplative life as a Catholic sister allows me to take a long and loving gaze in the mirror. As Saint Mother Theodore Guerin said, “If you lean with all your weight on Providence, you find yourself well supported.”

This lifestyle allows me to create space for people I meet along the journey who are searching for companionship as they struggle. I can be present for people who are stuck, whether from fear of the unknown or from a lack of opportunity. I can provide for people in deep need of faith, hope, and Christ’s loving light. Sister Jean Hinderer, C.S.A. once said about religious life, “I belong to everyone, and I belong to no one.”

My quest for God has lured me and led me to a life of fullness, the life I am meant to live. Yes, God speaks in mysterious ways! I decided to walk into the unknown around a mountain just off Highway 1 in California. And there, hidden behind the mountain, was a treasure. It was a deeper view of my heart. I saw the beautiful coast with rough and smooth edges, and I explored both my own intelligence and fragility. I found the treasure. I found the Sisters of Providence of Saint Mary of-the-Woods, Indiana, and they found me. I pray to our Provident God that we will never let go of each other.

Sister Jessica Vitente, S.P. is a campus minister at the University of Evansville. She took her first vows in August, 2021.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

FOR NEARLY 2,000 YEARS people have sought a distinct way to lay down their lives for Christ and the church through consecrated life. Their motivations are usually layered, with the full rationale for an entrance not always apparent to even the person involved. Still, vocation ministers for religious institutes want to at least know the motivations that people can name. With that end in mind, the National Religious Vocation Conference (NRVC) gathered information in two ways when it investigated what attracts people to religious life in its 2020 survey of newer religious. NRVC asked newer members of religious institutes to directly name what attracted them, selecting from several choices.

The top three choices essentially have to do with a desire for spiritual depth (spirituality, charism, mission); and community and ministry are close behind. Most of the survey respondents were under age 40, but a fair number were over 40, sometimes by many years, so the survey does not strictly reflect the thinking of young adults in religious life, although it approximates it.

To come at this complex question about attraction in another way, the 2020 study also asked religious who had been in an institute for 15 years or less to simply talk about their attraction at several focus group sessions. And talk they did. The transcripts of the study’s 13 focus groups amounted to hundreds of pages, with conversations touching on many themes. Themes from the survey answer choices showed up frequently, but other ideas also emerged. When left on their own to explain their personal attraction to consecrated life, respondents repeatedly told stories about their discernment that brought up these concepts:

• Joy of members

• Positive relationships among members

• Witness of members

• Meaningfulness of consecrated life

• Community life (eating, praying, recreating, ministering together)

• Shared ministry

• Totality of consecrated-life commitment

• Sense of belonging and feeling at home and at peace with the community

• Charism that resonated with them

Other themes not directly about attraction also arose as people tried to answer the attraction question.

• impact of particular encounters with people both in and out of religious life

• slowness of their own vocational understanding

• emptiness of career and material achievements and the desire for “something more”

• importance of spiritual direction and/or serious, regular prayer

To flesh out these points, here are the voices of respondents themselves in excerpted passages from study focus groups. (NRVC members may request a PDF of the full transcripts from the study focus groups by writing to mailer@nrvc.net.)

I was first attracted because of the examples of the sisters I had in school and in my community. Some [were] teachers in our school. [Others] ran a nursing home in my hometown and ran a retreat center out on the lake. So, I think the example they set of happiness, faithfulness, and service to God [made me] want that joy that they seemed to have.

I think the very heart of what attracted me to religious life was that it is a daily dwelling with God—every moment of being in [God’s] presence—and that everything in our life is ordered to that.

I studied abroad in Rome when I was in college. While we were there, a couple of us went to the countryside, not intentionally to visit a religious community, but our chaplain brought us to a religious community. And it was there [that] I was really struck by their community life; it was brothers and sisters and priests [who were] all part of one community. And the love between them … realizing it was all rooted in Christ. And that’s when I felt an invitation to that same love, if I would be willing to look at religious life.

I think for me, what really attracted me was community living, you know, their prayer life, the charism of the foundress, how she went out to look after women, she took women into her home, the vulnerable, the children.

I grew up Catholic, went to Catholic school, left the Catholic Church for 12 years as a young adult, came back to the church, and was really drawn to the social mission of the church, through peace and justice in particular.

What attracted me to my community was the witness of joy that our sisters had. I had a teacher who was from our community when I was a freshman in high school, and there was something about her presence. She had a joy that I had never seen anyone else have before. And

I wanted what she had. I wanted that joy…. I didn’t know how she had it, but I wanted it. So, she brought us to our motherhouse. And when I went there, the experience I had with the sisters, that initial experience… [I saw] joy and connectedness with Jesus and the Blessed Mother.

When I drove on campus, there were like 50 sisters … I’m thinking, “This is like Sister Act.” I just felt that sense of home, like I’m where I’m supposed to be. Just, kind of, everything fit. Ever since I was a little girl I liked being a teacher; that’s what our apostolate is.

After college I moved out, taught on a Navajo reservation. I met one of the sisters from our community out there. It was not the spiritual stuff [that attracted me], it was more of the faith through action. She was always doing things like cutting bushes, mowing grass, doing that kind of stuff, waxing, stripping floors. She’d ask for help. I could help with those things. Those were safe things. I kind of helped with that, cleaning the church, doing those different things. [I was] finding God in those things, kind of meeting her through doing those non-spiritual things. Faith in action is kind of what drew me to community, and it blossomed from there.

I felt this desire to do something more with my life than study economics and date the girls I was dating. A lot of them were sort of in a relationship just to fit in with other people, to fit into the college scene. I was sort of disenchanted with a lot of things. I just felt I needed something more.… I think what attracted me to the idea [of community life] was that I had known a lot of priests, and the idea of just being alone at night, or potentially being alone at night, or just being with one person in a rectory, it just seemed really unattractive for me.

I was attracted to the charism. I became a lay [associate] for a number of years. Then I started thinking about religious life because living on my own, it just felt like something was missing. I was attracted to living in community with other people with the same charism, with the same spirit, with the same hopes for the world [even] with our differences.

I saw men who are priests, but men who are, as religious, also doing other things as professors, as doctors, lawyers. That really attracted me, to be able to be a priest and to bring the Eucharist to people, but also to have a profession and to relate to people in other ways as well. I also had the opportunity to work in my community at my university.

I think what might have attracted me the most to this community was just that it seemed to fit. I could see myself there.

I started to go to spiritual direction with a [member of the community]. It was really learning how to pray in that tradition that attracted me to religious life, learning how to place myself in scripture imaginatively and realizing that God communicates through my internal movements and my emotions. That drew me to go to a discernment retreat.

This article draws from the 2020 Study on Recent Vocations, conducted by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate for the National Religious Vocation Conference. The full report, summaries, and other resources for exploring the study’s conclusions can be found at nrvc.net.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

The conclusions of a recently completed examination of the pastoral needs of youth and young adults are important information for all vocation ministers. The National Religious Vocation Conference was one of approximately 75 Catholic organizations that took part in an extensive, multi-year process of listening to the concerns of young people and those who minister among them. Representatives from the NRVC attended several meetings during this process, providing the perspectives of professional vocation ministers.

The conclusions are significant for two major reasons. First, they matter because the form and process that led to the conclusions of the National Dialogue were highly inclusive and exhaustive. It’s important to listen to what emerges from such a thorough appraisal. Secondly, the conclusions of the National Dialogue matter because one of the key things young adults are asking for is accompaniment in vocational decisions, vocation in the broad sense of the word, not strictly entrance to a religious order.

Vocation ministers operate from two platforms and often move seamlessly between them. On the one hand, they invite people into their communities and walk with women and men interested specifically in religious life. On the other hand, vocation ministers also walk with young people who are uncertain about life direction and want the wisdom of the church to help them live Christian discipleship in general, not necessarily discipleship as a consecrated person. The National Dialogue report is a strong reminder that young people desire this second form of vocation ministry.

Following are excerpts directly from the final report of the National Dialogue on Catholic Pastoral Ministry with Youth and Young Adults. Find the full report at

nationaldialogue.info.

In Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis inspires us to confront the status quo of pastoral ministry. All who are involved in pastoral ministry with young Catholics must take a hard look at the sobering realities we face. These realities include:

• Families who often lack the capacity to fully form their children in the faith

• Parents and other adults who continue to leave the church in significant numbers

• Youth and young adults who are frequently inarticulate about the faith

• Hispanic (and other) young people and families who regularly find a less-than welcoming reception or helpful pastoral services

• Youth and young adults with little opportunity for a quality education that will assist them in becoming meaningfully employed and fully participating citizens

• Youth and young adults who are on the margins of society and church due to delinquency, gangs, drugs, criminal activity, and/or poverty

The pastoral challenges posited by Pope Francis and revealed by discerning observation, demand new ideas, creative energy, and a commitment between both laity and institutional church organizations to work together to spread the Gospel with authenticity, compassion, and mercy.

An important aspect of the National Dialogue was to bring together different models, approaches, movements, and ministerial contexts involved in ministries to youth and young adults to identify a shared commitment amid different models and contexts.

The recommendations, based on the National Dialogue data and conversations, include the following:

1. More intentionally connect the life of faith with the lived experiences of young people.

The National Dialogue observed that even active young people feel the Catholic Church does not show how faith is relevant to their daily lives, transitions, and lived experiences.

2. We all need to do more synodal listening to one another.

The recent experiences of the Synod, the V Encuentro, and the National Dialogue show that synodality is essential, especially listening to those from the peripheries and bringing in the voices of those who are not around the table.

3. Address the “authenticity gap.”

The National Dialogue revealed that the church needs to show more empathy and authentic engagement with the young, rather than empty platitudes or impatient judgment of the young and the disaffiliated.

4. Increase the investment in accompaniment.

We do not walk alone, and we need each other. The National Dialogue, echoing Christus Vivit, saw that the church must train more people in “the art of accompaniment” with youth and young adults, especially in the area of mental health.

5. Expand ministry with young adults.

All age groups and conversations with the National Dialogue noted the church’s significant lack of attention to young adults (ages 18-39) and expressed a strong recommendation to increase, invest in, and expand this ministerial area.

6. Reimagine faith formation.

There was regular encouragement in the National Dialogue to move away from a classroom model and toward more relevant learning models featuring mentorship, small groups, accompaniment, faith sharing, and

authentic witness.

7. Reconsider preparation for the Sacrament of Confirmation.

There was a clear call to re-examine and reconsider how the church prepares young people for Confirmation.

8. Partner with parents and enhance family ministry.

Due to the concerns of ministry leaders and parents expressed in the National Dialogue, there must be increased dialogue and collaboration with families and the domestic church, including the growth of intergenerational/family ministries.

9. Transform ministry leadership.

It was evident in the National Dialogue feedback that the church needs to seriously address the formation, support, and resourcing of ministry leaders and create a culture of collaboration and unity across ministerial and ecclesial lines.

10. Embrace complexity.

Because of the plethora of findings from the data, and recognizing the needs of young people, families, and leaders are so vast, there is no “one size fits all” approach that can be taken; rather, leaning into this complexity is highly recommended.

• The young people in these conversations are actively engaged in their faith, yet still struggle with the church.

• There is incredible diversity among youth and young adults in terms of culture, ecclesial perspective, spirituality, and lived experiences.

• An awareness and responsivity to this diversity may at times be lost in ministries with a diverse community of young people.

• Young people and ministry leaders want more listening as was found in the model of the National Dialogue, the V Encuentro, and the Synod.

• The participants, by and large, wanted to see church leadership and their fellow Christians be more authentic and less judgmental and divisive.

• The young people in these conversations have a very strong sense of mission; they want to change the world.

Youth asked the church for:

a re-imagining of faith formation and Confirmation preparation, away from a classroom model

greater intergenerational support, dialogue and mentorship

more youth ministry programming

Young adults asked the church for:

a more integrated and relevant approach to faith and everyday life

more guidance and accompaniment during young adult transitions and vocational discernment

more ministry opportunities for them as young adults, inclusive of increased funding and support for this ministerial area

As young adulthood is a time of great transition, young adults want to know—from the church—how to best discern God’s call. The young adults themselves noted that discernment needs to be deeply enmeshed in the church’s ministry with their age demographic, and not just regarding priesthood or consecrated religious life; rather, discernment was called for in a broader sense. The young adult conversations discussed the need for the church to accompany them through the transitions in their lives, such as the journey from youth to young

adulthood; graduations (high school to college, college to the working world, etc.); new jobs and career paths; constant geographic movement and migration; serious relationships, engagements, and marriage; and parenting, among other major moves.

There is a strong call for mentorship and accompaniment, similar to what was asked for by the youth; however, in this context, it was focused on mentorship through those transitional experiences. The call for a cultivation of friendships and accompaniment pointed toward fostering peer relationships of support and accountability within church settings. This was echoed by the youth and ministry leader participants in the National Dialogue, but was heard strongest from the young adults.

Read the full report at nationaldialogue.info.

Excerpts reprinted with permission from National Dialogue on Catholic Pastoral Ministry with Youth and Young Adults Final Report, nationaldialogue.info.

The National Federation for Catholic Youth Ministry (NFCYM) digital assets contained in this work are used with permission and do not imply an endorsement by NFCYM.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

IF I COULD WRITE TWO WORDS on my tombstone, they would be, “She laughed.” I want to leave behind a legacy of joy, a smile for the world, and giggle of glee at the very mystery of life. I don’t know when my last breath will come, but I do know that in this moment, I want to breathe in the goodness of God and bask in the oil of gladness. I want to play as fervently as I pray and laugh as heartily as I take up my daily tasks. In this way, I know that the fullness of life is within my grasp and the kingdom of God is as close as my hand.

Let’s face it: life is serious. The realities facing our world today in this time of turmoil, violence, natural disaster, isolation, and sickness can steal our joy. In the midst of it, healthy humor, laughter, and play need a place on our community agenda if we are going to survive. As Pope Francis has repeatedly proclaimed, “The world doesn’t need any more Christian sourpusses!” All the more, people in discernment need to be in touch with the lighter side of life. Certainly the challenges that our next generation of men and women religious will face are daunting but not impossible. If people don’t witness our individual and communal spirit of joy, they may see priesthood and religious life as emotionally demanding, energy-sapping, and lonely. We have the creativity and enthusiasm to draw others into our way of life and help them to re-connect with a genuine joy in the Lord.

I recall a rather animated exchange with my college roommate’s Italian mother when she discovered that I was planning to become a sister. With tears in her eyes, she muttered, “But you like to have fun! How are you gonna make it in the convent?” I assured her that I’d seen the lighter side of life in the convent and that the sisters I knew were actually quite full of fun. One of my fondest memories was of the day my “sisters-to-be” took a three-hour drive to visit me while I was spending my summer as a Girl Scout camp counselor. That particular day, was “Backwards Day.” We were wearing our clothes backwards and eating our meals from dessert to salad. My visitors greeted me with smiles, admiring my backward attire and enjoying brownies as a first course. Later, they donned giant garbage bags when the skies opened up and poured rain on us. That was the day I knew that this was the community for me. After all, a community that plays together stays together.

Fast forward 33 years. When I was vocation director for my congregation, the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth (C.S.F.N.), I had the privilege of helping discerners tap into that same wellspring of joy and find a key to the door to peace and freedom of heart. Discerners frequently come to the discernment process carrying burdens. Resistance from family and friends, feelings of insecurity, anxiety about finding the “right” community, diverse theological or spiritual perspectives, concerns about debt and finances—these are just a few factors that add to the seriousness of someone discerning a religious life vocation. Finding healthy ways to defuse the tension helps discerners to relax and redirect their energy to create new perspectives and broaden their horizons.

In keeping with this philosophy, the schedule for one of my community’s “Come and See” days or discernment weekends included (in addition to prayer, quiet time, and small group discussion about vows and community life) singing, games, cooking together, watching movies, artistic expression, and community service. Occasionally someone might ask why we would spend valuable time on seemingly “frivolous” things when the discerners are with us to learn about religious life. The benefits of these playful activities far outweigh the concern that the discerners will go away without receiving sufficient understanding of the ways of religious life. In fact, the opposite is true.

Discerners who are able to relax, laugh, use their creativity, and expend physical energy during a discernment experience are more willing to come back for a second look. If members of the religious community join with the discerners when possible, the positive effect doubles. Healthy, animated interaction and a spirited sense of humor among community members are attractive qualities for discerners to witness. They also increase the bonds of communion. Opportunities for informal conversation during times of play create an environment of trust and openness and often lead to the formation of deep and long-lasting relationships.

For the vocation director, seeing and experiencing someone “at play” provides valuable insights about the discerner that other assessments might overlook. Observing a discerner’s sense of humor and play opens a window into the personality. For example is the discerner’s sense of humor laced with sarcasm, cynicism, sexism, racism, or self-deprecating innuendos? Does the person use humor to avoid conflict or to mask feelings of inadequacy? Is the person’s humor appropriate to the situation? Does an overly-heightened sense of humor indicate anxiety? Does the discerner generally have a joyful, peaceful disposition? Is the discerner able to analyze situations and find humor in the sometimes topsy-turvy events of daily life? Is the discerner able to pick up social cues and understand when humor is inappropriate? Can the discerner appreciate and understand the humor of others? Does the discerner take offense at the humor of others (assuming that it is appropriate to the situation)? Does the discerner use humor to draw attention to him or herself rather than using it to engage others and stimulate conversation? Does the discerner react negatively to humor or find it “childish”? Is the discerner able to find humor and play in the context of sacred scripture? Does the discerner’s image of God point to a God of gladness and joy who delights in people and gently forgives their sins and shortcomings?

The answers to these questions provide insights about discerners’ basic dispositions, about their images of God and religious life, and about their approach to handling the situations that life brings.

Recreational and service experiences provide an opportunity to see how discerners interact socially and participate in community. Discerners often use these opportunities for healthy self-disclosure. I have learned more about a discerner as we weed a garden together, fly a kite, or discuss a movie than I sometime can in a more formal interview. Discerners with self-esteem issues, depression, or other social inadequacies often decline to participate in group play or work experiences and may appear distant or isolated from the rest of the group. With encouragement, some of these discerners are able to experience increased trust and willingness to take initiative when other discerners and community members lovingly draw them into the activity. Recreational and service opportunities provide common ground for a group of discerners and allow them to problem-solve, use their creative resources, test their communication skills, and share faith with one another. Through play and interaction, the vocation director can assess a discerner’s social strengths and community building capacities. These indicators are crucial at the beginning of a candidate’s journey in initial formation when he or she is striving to bond with the community and offer his or her gifts for the common good.

In a 2011 baccalaureate address given at the University of Pennsylvania, Father James Martin, S.J. reminded his listeners that “joy, humor, and laughter are under-appreciated values in the spiritual life and represent an essential element in one’s own relationship to God.” He goes on to state that humor is a tool for humility. When we can laugh at our own foibles and eccentricities, our ego is kept in check and we can be more open to transformation.

Humor can also speak truth to power. If we look at the Gospels with the lens of humor, we will see that Jesus used humor to ensure that his message would not go unnoticed. With a wink and a laugh, Jesus disturbed the comfortable and comforted the disturbed. Eating with sinners, washing feet, stopping a would-be stoning, calling men out of trees or telling them to walk away from their life’s labor are just a few examples of Jesus’ unique humor and perspective. It’s easier to change the world with an injection of laughter than with an infusion of force.

Joy is an important part of our relationship with God. God invites us to be friends, to be intimately known, loved and blessed. As we grow in genuine friendship with God, we fear less and trust more, and we discover the secret of adding lightheartedness to our spiritual life.

On a practical note, I have applied these notions in a concrete way in vocation ministry. One of my best discernment weekends ever took place October 30-November 1. Since the weekend encompassed both Halloween and All Saints Day, we took advantage of two fun ideas for our evening recreation.

In an activity designed to develop the concept of uncovering our true identity and owning our false self-images, participants were given a white face mask and were instructed to draw a line down the center of the mask, from forehead to chin. On the left side of the mask, they were asked to draw symbols and images of the false self that they desired to shed. On the right side of the mask, they were asked to draw symbols and images of the face of Christ that they desired to put on so as to grow in holiness and true knowledge of self. After time to work on masks, everyone came back together for group reflection. What followed was a deep, powerful sharing from the heart. Given that just 24 hours earlier, these women were almost complete strangers to one another, the proof of the power of play and creative expression was tangible.

A second activity, pumpkin carving, found participants gathered around tables, assisting one another in designing and carving their pumpkins. Another group worked on sifting through the pumpkin insides to pull out seeds for roasting. When all the pumpkins were prepared, we placed candles inside each pumpkin and turned off the lights to see the beautiful works of art. In reflecting on this activity we noted that in order to be God’s light in the world, we first had to sink our hands into the messy inside of the pumpkin, pulling it out and straining it to separate the seeds. We noted that even in the messiness, the seeds of goodness can be found. As the inside of the pumpkin was cleared, we talked about the necessity of removing blocks so that the light might shine through the holes and cracks to reveal something beautiful. Even though the atmosphere was playful and light-hearted, the activity brought many in the group to tears as they acknowledged where they were on the continuum of spiritual growth and self-understanding.

We ended with cupcakes prepared by one of the discerners. They were decorated and topped with cookies to resemble tombstones. As we enjoyed the sweet treat, participants were invited to share with the group what they would like to have engraved on their tombstone. We laughed at some of our silly responses, but later acknowledged that we’re all “saints-in-the-making,” called to leave our mark on the world. We prayed a litany of the saints, calling upon heroes in our faith history and in our personal history, asking them to surround us and fill us with courage and strength to do great things for God.

Opportunities for play and fun are all around. Here are some ideas:

• Can you arrange virtual or in-person access to a nursing center where discerners can visit with the wisdom figures of your congregation?

• Does your community have artists, writers, or musicians who can share their gifts and help discerners to draw upon their creativity?

• Are there special liturgical feasts or holidays that can be a springboard for creative ideas?

• Can community members participate in recreational or creative initiatives, online or in-person? There are ways to play Pictionary, Jeopardy, and other games using Zoom.

• Does your congregation have a garden or other outdoor seasonal work— anything from raking leaves to shoveling snow—that participants can work together to accomplish?

• Is there space for discerners to collaborate in a cooking project, such as making soup or baking cookies? Afterward could they distribute the results to a group or individuals in need?

• Does your congregation have a special mission with the poor that discerners could participate in?

• Is there a film or show with themes related to discernment, social justice, or the community charism? Consider hosting a viewing and discussion.

• Do you have access to a gym or another indoor or outdoor facility for physical activity, team sports, or other recreation?

Of course it’s also good to take advantage of spontaneous opportunities for fun. Many times discerners themselves will find ways to use their creativity and humor during their free time or in response to an activity. Let the Spirit lead you. Relax and try to draw others, particularly your own community members, into the fun. Most of all, enjoy the lightheartedness that comes when brothers and sisters work, pray, and play side-by-side and attract others to share in the gift that is religious life.

A version of this article appeared in HORIZON 2012, Summer, No. 3.

“Laughing with the saints,” by Father James Martin, S.J. HORIZON 2009, No. 2. Find this article and more at the HORIZON online library, nrvc.net/horizon_library.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

AFTER AUGUSTINE AND HIS FRIENDS had been baptized, they set out to return to Augustine’s hometown of Thagaste in North Africa to establish a way of life based on the Jerusalem community in the Acts of the Apostles. The Thagaste community quickly gained a fine reputation as “servants of God,” attracting new members from near and far. The story is told that it was an inquirer from Hippo that first brought Augustine to the city, changing his life and ultimately changing the course of history. Staying in Hippo for some time as he discerned with this individual, Augustine hoped to bring the inquirer back to Thagaste to join the community. Instead, just the opposite happened: Augustine caught the attention of the Christians there who “seized him” after recognizing his gifts, “called him forth” to minister as their presbyter, and “dragged him” to the altar for ordination, though he himself was admittedly reluctant, even to the point of tears. (See Augustine’s Sermon, 355.2, for his own reflection on this dramatic occurrence, as well as his friend and biographer Possidius’ Life, 4.)

It is not an understatement to suggest that had Augustine not gone to meet with this discerner, well, the church simply would not be the same. Consider the rich sacramental theology offered in his Easter sermons, his articulation of a theology of grace; his classic spiritual autobiography Confessions and his Rule, which, to this day, is a foundational document for countless religious institutes of women and men—all of this resulted from his coming to Hippo for the purpose of vocational discernment. Could this have been the fruit contained within the seed that he thought he was planting in that conversation with the inquirer? Could Augustine’s accompaniment of the individual have also been about the way God was nurturing Augustine’s own vocation?

It seems that the answer is a resounding yes. However, it begs the question of how much Augustine actually knew he was getting himself into when he agreed to go to Hippo. He simply wanted to welcome and accompany a new member to his community, but there was a certain “publicness” that came with that desire, the public witness of his own vocation.

This event serves as a cautionary tale for all vocation directors—one never knows where or what vocation ministry might lead to. On some level, we all know that one new member can change things, or at least that is what we tell ourselves, but to have one new member actually have such an impact that it changes our own trajectory, our own direction, putting us into a new place and space, is a prospect that is difficult to fathom and grasp, let alone desire. I can imagine some members of Augustine’s community in Thagaste asking him this question when he agreed to set out for Hippo: “Do you clearly understanding what you are undertaking?” And it is one that may sound familiar, as it has baptismal echoes.

“You have asked to have your child baptized…. Do you clearly understand what you are undertaking?” This is the question posed to parents and sponsors of a child at the entrance of the church at Baptism. I always laugh to myself whenever I reflect on this important moment at the beginning of life in the church, as parents and godparents seem to give their assent so quickly. In fact, I sometimes wonder if they even really pay that much attention to the question, not only because they are distracted by the baby in their arms coupled with their excitement for the day, but the very weight of the question could be too much to bear and take in.

If that is the question asked at Baptism, then with religious life as a marked intensification of this sacrament, imagine its weight on the mentor of a discerner and new entrant. Do you clearly understand what you are undertaking in vocation ministry? Do you clearly understand what is being asked of you by God and your community in walking with someone who is discerning religious life, a deeper expression of Gospel living begun at Baptism? Do you clearly understand that your life can be significantly altered, as was Augustine’s, bringing you to a new place in your own life and your own understanding of your yes to God? Do you understand? Clearly?

The answer, of course, might be a comfortably Catholic one: a resounding yes—and no—which makes for some obvious discomfort. To what extent does anyone understand clearly what they are undertaking when it comes to any commitment in life, let alone the nurturing and mentoring of a new member of a religious institute? Those entering our communities might understand they are undertaking the Gospel journey, a journey that will call forth gifts, seize them, and drag them reluctantly at times into a life not yet imagined and a future not yet revealed. This is not to discount the need for garnering good information from mutual discernment. But, when it comes down to it, one will not—and cannot—have every aspect, or every impact of the religious life commitment figured out. It is not the way life works, and it most certainly is not the way life with God works, no matter how intentional, prayerful, and discerning that life is.

There has to be some room for Mystery marked by trust. Again, on some level we know this to be true in theory; yet, on another level, it is a practice in, what Augustine calls at the end of his Rule, “living in freedom under grace.” And this spiritual practice is self-implicating, just as Augustine demonstrated. In other words, there is something about life in and with Christ, particularly as expressed so intently in religious life, that is more about the embrace of the unknown than the known. If we are going to invite others to join in our company and mentor them, then we have to be willing to continue going into the unknown ourselves. We need to enter into the unknown at the prompting of newer members. Could this be one of the gifts that religious life can offer to the world in our day? Could this risk-taking be what we clearly know that we are undertaking?

It is safe to say that this embrace of the One who is both known and unknown—as expressed particularly in a call out of the depths and into the depths—has always underpinned religious life through the ages. But there is something about life and church in the 21st century that asks us to “return to the source(s)” in a newer, fresher way, or with a greater emphasis, perhaps different from what we thought Vatican II asked of our communities, though Vatican II’s invitation may very well have prepared us for this moment. It could be the shrinkage of many of our communities; it could be the abuse crisis within the church and the mistrust of institutions and authorities; it could be the increasing none-ing and done-ing of religion coupled with an embrace of seemingly untethered spirituality; it could be what the new cosmology offers us as we become more aware that we participate in an unfinished universe. More than likely, it is a combination of all of these, which together pointedly ask of us, “Do you clearly understand what you are undertaking?”

I would suggest that the response to this question speaks of a dynamic tension from the contemplative tradition. All our religious institutes have been born out of contemplation to varying degrees; one might even say that the communities and their respective charisms resulted from the tension itself that contemplation holds. What the contemplative tradition underscores is the necessary embrace of Mystery in our lives, in our “real presence” encountering and in dialogue with Real Presence; it is Eucharistic in its expression. And, true to its Greek root, mysterion, mysticism, as the undertow of this tradition, implies a hiddenness and mystery begging to be noticed and made known.

Too often this has been seen as the work and call of an elite few. Some might say this makes the understanding of this hidden mystery inaccessible to the majority, but that is a terrible misreading of the tradition. Instead, these canonized mystics (i.e., canonized as in part of an official list, not necessarily saints) could be seen as the women and men gifted with an ability to articulate, or attempt to put into words, the “deep calling on the deep” waters of our Baptism, which is not to diminish nor discount their own unique, personal, and intimate experience of God.

For those tasked with accompanying inquirers to religious life, mysticism’s articulation and navigation of the spiritual life offers helpful tools. Both Teresa of Jesus of Avila and John of the Cross, for example, offer particular insight here. At the very beginning of the Book of Her Life, often referred to simply as her Life or Vida, Teresa appeals to claridad, clarity, which she couples with truth. She writes, “May God be blessed forever, He who waited for me so long! I beseech Him with all my heart to give me the grace to present with complete clarity and truthfulness this account of my life which my confessors ordered me to write. And I know, too, that even the Lord has for some time wanted me to do this, although I have not dared. May this account render Him glory and praise” (Life, Prologue, 2). While scholarly input has revealed several layers of Teresa’s motivation, authority, and voice in her own right, one characteristic of Teresian spirituality could be seen as this search and desire for clarity, that is, to understand, to put into words, and to name her experience of God. Teresa clearly knew this need in discernment, in not only her own self-presentation but in how she was received and perceived by others. She desired authenticity without deception. Her appeal to complete clarity and truthfulness could be understood as both an examination and manifestation of her interior life, which she was clearly trying to understand and articulate herself, as well as a request to her audience to be open to what she had to say.

At the same time, she highlighted the importance of mutuality in this process and spoke of her struggle in trying to find this mutuality. She expressed a need for those who accompany, mentor, and guide others to be in touch with their own experience. She often felt a lack of understanding from those who initially guided her (or even those to whom she confessed frequently) because they were not grounded in their own experience or simply had not done the interior work themselves. Teresa’s frustration speaks of the truly self-implicating character of guiding and mentoring someone in discernment, whether as a vocation minister or as a spiritual director. Even so, we could say that her frustration nonetheless compelled her to be as clear as possible—to search for the right, fitting words—so that the one who accompanied her could understand.

What Teresa can offer vocation ministry is twofold: first, create the space so that the one who is discerning has the freedom to express his or her heart’s desire in a clear manner; and second, in making this appeal to clarity, note any experience of frustration or resistance on the part of the inquirer and/or the vocation director, for this felt tension might reveal something begging to be noticed in the discernment and very well may be the entry point to something not yet named. As an aside, perhaps like Augustine, little did Teresa know what she was getting herself into, when first entering Carmel of the Incarnation—admittedly because a friend was entering!—and when 20 years later something new was stirred in her prayer life that would propel her into a deepening conversion, ultimately reforming her way of life. No wonder Teresa desired good accompaniment during her vocational journey!

Often rightly seen as her companion in the spiritual life and in the work of reform, John of the Cross offers another nuance helpful for vocation ministry. Like Teresa, his experience of religious life took him to places he was not expecting. Consider, for example, how it was his own brothers in community who imprisoned him, placing him in isolation, confinement, and physical darkness, yet it became the space from which John composed some of the most beloved poetry of Spain’s Golden Age, such as “The Spiritual Canticle.” In fact, some might argue that his time of imprisonment became a source of ongoing reflection and subsequent commentary to his poetry.

At the beginning of his poem, “I Entered into Unknowing,” John suggests that unknowing is a way, even the way, of knowing: “I entered into unknowing, yet when I saw myself there, without knowing where I was, I understood great things.” Granted, these lines speak of an intense, mystical experience, not meant to be over simplified nor impoverished of meaning, but there is also an invitation in these words that is accessible to all. Among the learned of his day, John struggled with the privilege that having such intellectual leanings and credentials brought. Could the stirrings of his own inner life have been a way of navigating this struggle, while encountering the presence of God? Perhaps. What John also offers is the attraction and the embrace of the nada (or “nothing,” notably different from Teresa’s “Let nothing disturb you…”). Negation brought John of the Cross into greater freedom, whereby he was moved to let go of what held him from going deeper still. In other words, the insight here is that sometimes our own knowledge, or what we think we know (of ourselves, God, others, the world) can get in the way of what God may really want us to know.

This insight from John can be a focus of further reflection in vocation ministry, for both inquirers and vowed members alike, as we navigate new currents in religious life for the 21st century. Inquirers can sift through what they believe God is asking of them. Vocation directors have countless stories of women and men who enter into discernment with sometimes unrealistic expectations and assumptions. Coupled with Teresa’s call for clarity, the vocation director could mentor an inquirer in John’s practice of unknowing and unlearning as a way of knowing, learning, and deepening his or her discernment. How might we engage these individuals in such a practice that is respectful, challenging, and sacred?

What the contemplative tradition offers is a way not only to ask the deep questions of vocation discernment, but more importantly a way to sit with and ponder them, holding both the question and the answer in sacred tension. We would do well to express early on to discerners this contemplative dimension of life in Christ—the call of all the baptized. We see this contemplative dimension accentuated particularly in the lives of our charismatic founders who dared to set sail in new ways on the baptismal waters as they answered their own call. It was Augustine’s call. It was Teresa’s. It was John’s. And it is ours. Clearly.

Father Kevin DePrinzio, O.S.A. belongs to the Augustinians. He is vice president for mission and ministry at Villanova University. He served in vocation ministry for his institute from 2007 to 2012, during which time he served on the board and as a regional coordinator for the National Religious Vocation Conference.

“Walking with someone in discernment,” by Virginia Herbers, Winter 2020 HORIZON, No. 1.

“Ignatian discernment: insights for you and those you serve,” by Father Timothy Gallagher, O.M.V., Summer 2018 HORIZON, No. 3.

Published on: 2021-11-02

Edition: 2021 HORIZON No. 4 Fall, Volume 46

ABOUT 10 YEARS ago I attended a workshop in London on evolutionary consciousness. One of the speakers used the term “the adjacent possible” to partially describe the dynamic of the evolutionary process. I could immediately see people writing down that phrase. It seemed hopeful and not too heady. Something was adjacent, right there beside us, and it was possible. The presenter, Carter Phipps, spoke about how every audience he had been with prior to our workshop responded exactly as we had. They and we wanted to hang on to that phrase. It is as if there was a collective call to new horizons in the audience. To give credit where due, the phrase originated with Stuart Kaufmann who used it to describe biological evolution.

Consider your own experience and your own institute or congregation, not to mention our world as you read the quotation from Stuart Kaufmann below.

The adjacent possible is a kind of shadow future hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways in which the present can reinvent itself. The adjacent possible captures both the limits and the creative potential of change and innovation. The strange and beautiful truth about the adjacent possible is that its boundaries grow as you explore them. Each new combination opens up the possibility of other new combinations.